Primitive worms threaten harvests

They live in the soil, are numerous, and can be microscopic. Yet nematodes can effectively kill off fruit trees and cereals.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

What multicellular animal organisms are so tiny that you can find 38 million living in one square metre of grass turf?

The correct answer is: Nematodes.

They are also known as roundworms and are usually less than a millimetre in length.

Nematodes are found in nearly every ecological niche imaginable, from the poles to the tropics. Scientists have found them in cracks in the rock at the bottom of South Africa’s deepest mines. They thrive 1,300 metres below the Earth’s land surface – deeper than any other multicellular life on our planet.

And - bad news - some of them now pose a threat to global human food supplies.

Fantastic creatures

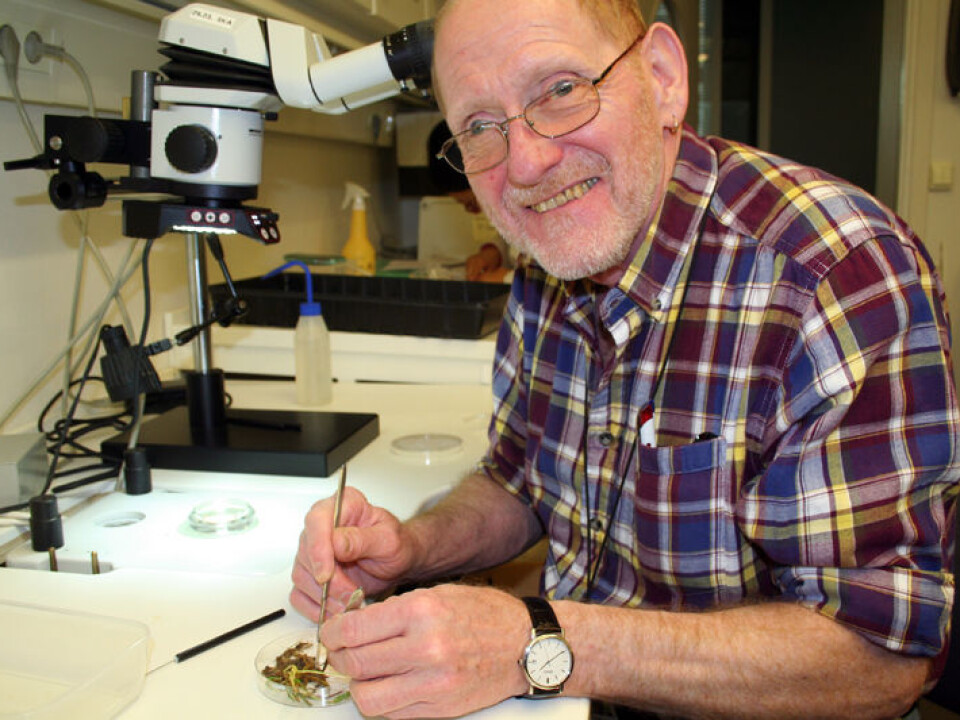

“These are fabulous creatures. The special thing about nematodes is that they represent immensity in something minute,” says Christer Magnusson, research manager of the Norwegian Institute for Biological and Environmental Research, Bioforsk.

He has spent most of his professional life studying nematodes and doesn’t regret a single day of it.

He remains engrossed by the subject of nematodes. Nematology, the study of plant nematodes, is a fairly young science compared to the study of plants or insects. So new research ground is continually being broken.

“It’s like a fairy tale. New things are constantly being discovered,” says the enthusiastic Professor Magnusson.

Damage is immense

But there is less joy about the damage that nematodes can do. Many of the at least 25,000 nematode species live as parasites on plants. In contrast to most insect pests and plant diseases, these pests take control over the growth of host plants.

Plant roots are a prime target and by manipulating a plant they can convert parts of the root system into ideal digs for themselves and their kind.

The hookworm is a highly unwanted pest in fields and lawns. It zeroes in on grasses, including barley, and causes their roots to swell. The resulting hook-shaped swellings are called root galls or root knots. They can each house thousands of nematodes in various stages of life along with myriads of eggs.

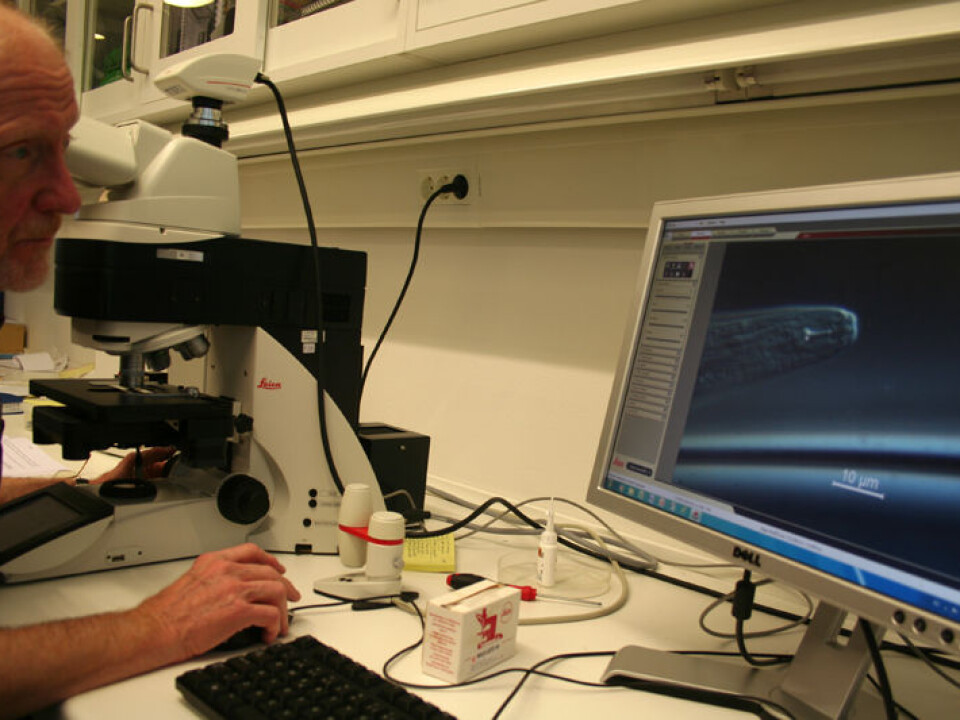

Magnusson brings out a prepared sample so that we can view an adult nematode in all its glory.

Using 2000 x magnification we can see the simple feeding organ the nematode inserts into plant cells. Its internal organs are clearly visible in its transparent body.

This elementary biological design has been functioning well for several hundred million years.

“Its primal ancestor must have lived on the supercontinent Pangaea before the dinosaurs. Nematodes are found on all continents,” he says, while peering through the microscope.

More vulnerable

Lawns and football pitches can be at their mercy. Grass suffers when its roots are attacked. One example is the arena where Norway’s national soccer team plays home games. The entire pitch had to be replaced in the 1990s because of a nematode attack.

But soccer is only, in the words of Norway’s former coach, “the most important of all the unimportant human activities”. A much more serious problem for humankind is the ability of nematodes to interfere with agriculture.

It is hard to quantify the damage, because that would require taking samples in innumerable fields the world over. But in the worst cases, nematode attacks cut crop outputs by half.

An effective battle against just one species, the cereal-cyst nematode, would mean a huge boost to harvests and farm income.

The warmer climate that is anticipated as a result of climate change will probably make agriculture in cold winter countries like Norway more vulnerable. Nematodes cannot tolerate much frost, but milder winters will enable more of them to survive.

“Generally speaking, the number of reports of nematode infestations is on the rise. We don’t know whether this is because people have become more conscious of them or whether there really are more nematodes,” says Magnusson.

At the same time, the availability of plant varieties, including wheat, that are resistant to nematodes is on the decline.

Cooperation with China

The global loss of crops due to nematodes can be huge, making the worms a major factor in affecting food supplies round the planet. Species as different as wheat, tomatoes and bananas can be infested. Some nematodes attack trees.

China is keen on collaborating with nematode researchers in Ås. Magnusson says that China has several million hectares of wheat fields today where nematodes are reducing harvests.

Nematodes weaken the root system of plants, which can be particularly critical during droughts.

Pesticide sprays have been used to control nematodes but environmental concerns have led toward the phasing out of these kinds of chemical solutions to the problem round the world.

Magnusson says that the best thing to do to stop nematodes that live in soil is to treat the soil with steam heat. Other efforts to halt their spread include rotating crops on agricultural land.

In poor countries with minimal resources, one of the challenges is finding ways to spread knowledge to peasant farmers.

Increased interest

Bioforsk has Norway’s only specialised research group in the field of nematology. These researchers are a small and vulnerable bunch.

Magnusson, who is also a professor at the Norwegian University of Life Sciences in Ås, has been delighted to see an influx of new students this year.

“We are facing a very serious situation. So it’s brilliant that we are getting more students,” says Magnusson. He stresses that new researchers need to be recruited to conduct fieldwork as soon as possible.

------------------------

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no

Translated by: Glenn Ostling