Valuable secret hidden in codfish ear collection

Cod have annual growth rings in the bony structures in their ears. Scientists in Greenland have collected these structures for nearly a century and have made a discovery that could help avert a new fisheries collapse.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

Yes, you read correctly: fish have ears.

And the Greenland Institute of Natural Resources, or Pinngortitaleriffik as it’s known in the Inuit language, has one of the world’s largest collections of the bones from codfish ears.

These bones, called otoliths, might not seem like the most useful thing to collect, much less like something that could provide helpful information, but it turns out that the Pinngortitaleriffik's mammoth otolith collection contains surprisingly useful information.

Scientists say the otoliths provide a unique window on codfish stocks and their health.

Nearly a century of otoliths

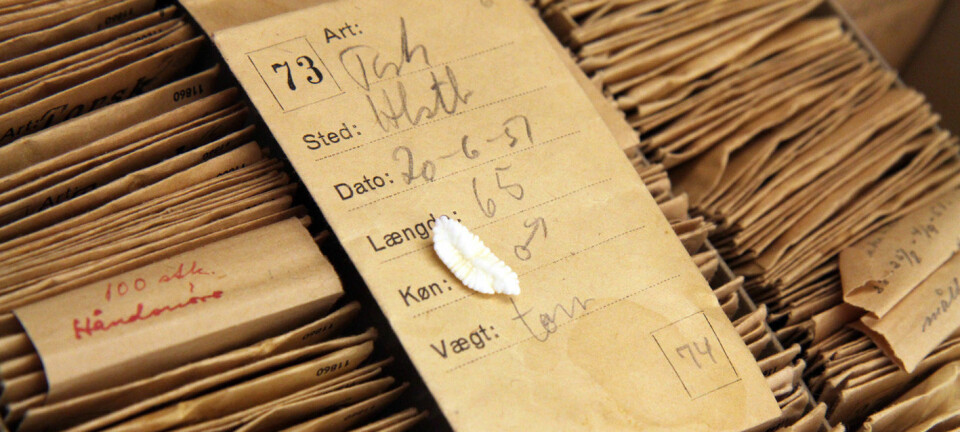

Shelves of cardboard boxes contain thousands of small, brown paper envelopes full of otoliths. The oldest is from the 1920s. Each envelope is marked with information detailing when and where the cod was caught, and how big the fish was.

The otoliths look like shells – they're white, slightly bowed structures that are sensitive to gravity and linear acceleration.

It’s been known for years that otoliths accrete a new layer of calcium carbonate annually. Just like the age of a tree can be determined by counting tree rings, the age of a fish can be determined by counting the layers in the otoliths. Researchers can also see the difference between good and bad growth years by the amount of growth in each layer.

Nina Overgaard Therkildsen, a Danish researcher currently working at Denmark’s National Institute of Aquatic Resources (DTU Aqua), had a sudden flash of insight when she stumbled across the collection.

What if these bones could tell the history of the Greenland cod, and why the fish all but disappeared in the late 1980s?

Blood and tissue revealed four groups of cod

Otoliths often have a yellowish coating, which consists of blood and tissue that stuck to the bone when it was removed from the fish's head. This dried residue provides a source for DNA samples.

“I knew there was DNA on the otoliths and that other scientists had used it to analyse approximately ten genetic markers,” says Therkildse.

“But I didn’t know whether it was possible to analyse variations in hundreds of genes simultaneously, using methods that had never been tried with historic fish samples.”

The short version of the story is, yes, it’s possible. The otolith collection was able to supply enough material to allow Therkildsen to chart a genetic map of the cod in Greenland waters over the past decades.

When the analyses were compared with the DNA from contemporary cod, she found that there is not just one type of Greenland cod, but four.

Different spawning grounds, different resistance

Greenland cod were thus divided into four sub-groups that do not spawn with one another. Two of these sub-groups spawn on the fish banks off the coast, while a third fertilises its eggs in the fjords.

The fourth group probably spawns off the coast of Iceland and drifts as fertilised roe and larva to Greenland with ocean currents.

“The amount of cod around Greenland has varied enormously. If we want to know how climate variations can impact the fish, it’s important to know where the fish caught around Greenland have come from,” says Therkildsen.

The different cod stocks spawn in different places and are thus probably adapted to different environmental conditions.

“This means that at certain times, some of the stocks will thrive while others are threatened by overfishing or environmental conditions that are unfavourable for them in particular. If we want to maximise long-term catches it would be smart to fish the stocks that are thriving at a given time and protect the ones that are struggling,” says Therkildsen.

New cod related to the old

Greenland experienced a cod boom on its west coast in the 1950s and ‘60s, but then the stock collapsed quite suddenly at the end of the 1980s.

This stock is now slowly being built up again.

“Some of the new cod come from East Greenland, but our results indicate that some of the cod are related to the ones found there during the big cod boom,” Therkildsen says.

“This indicates that at least to some extent we have growth of a local stock, rather than migration from Iceland, for example.”

Protection and fisheries

If Greenland cod spawn in Iceland it hardly matters how many are caught in Greenland waters. These are not the fish that will create the next generation.

But when fish in Greenland waters are actually spawning in those waters, fishermen will need to be more cautious.

“When we know these are Greenland spawning cod, we can be careful to ensure the protection of the spawning stock, rather than fishing as much as possible because they are Icelandic fish,” says the researcher.

The discovery has had an impact on the daily life of researchers who monitor Greenland’s cod stocks, and have offices in the same building as the ear bone collection.

“Pinngortitaleriffik has changed its routines. Now we issue separate biological advisory warnings and set separate quotas. This means we can permit fishing in the fjords while protecting the fish out on the banks, where the stocks are starting to make gains,” says Therkildsen.

---------------------

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no

Translated by: Glenn Ostling