More fish found deeper in the ocean

The amount of fish in the world is being reassessed upwards. Some ten billion tonnes of fish that live at depths down to a kilometre are not fished at all. A University of Bergen professor thinks this biomass will be much more important for humankind in the future.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

You might be under the illusion that the most abundant fish in the ocean are the ones that are most popularly fished, such as cod, herring and anchovies.

Not so. The greatest species and varieties of ocean fish currently swim in peace – at least in peace from the planet’s supreme predators, us.

Deep in bountiful waters such as the Norwegian fjords, and particularly in the open oceans, all sorts of fish are thriving which we never see on ice shavings in markets or processed into fish sticks. A new study shows there are far more of these fish than marine biologists believed.

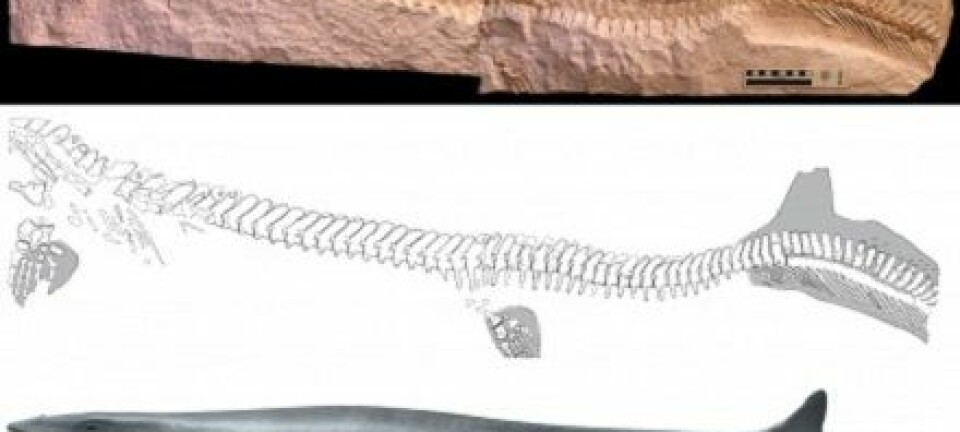

Depths of 200-1000 metres are the realm of mesopelagic fish. They tend to be small, from 1 cm and up to 15 or 16 cm in length, and they are hard to catch.

They have not been studied much by scientists and are totally unknown to most of us. Varieties in Norwegian waters include Mueller’s bristle-mouth fish and various sorts of lanternfish.

Feeds, oils – or food for us?

Can these fish be commercially exploited someday by the fisheries industry to make feed for fish or livestock, oils or food for human consumption?

A change in the resources we take from the sea will evolve, slowly but surely, and out of necessity, according to Professor Dag Aksnes of the University of Bergen’s Department of Biology.

“Population growth on the planet and rising living standards for more people are factors that put pressure on global fish resources. We already catch many of the fish on top of the food chain, and the general picture in fisheries as we define them now is stagnation,” Aksnes says. “Altogether the industry catches about 100 million tonnes a year. But it cannot catch much more than that."

Good at avoiding fishermen

He points out that there are exceptions, including along the Norwegian coast where cod fishing has been excellent lately.

Aksnes is a marine biologist and one of the few in his field who has conducted research on small deep-water fish since the 1990s. He has been joined in his endeavours by Professor Stein Kaartvedt of the University of Oslo.

In 2012 Kaartvedt and colleagues demonstrated that Mueller’s bristle-mouthed fish and lanternfish in the waters of Masfjorden create light that makes them virtually invisible to their marine enemies. The researchers also saw that these fish were nearly as good at avoiding fishermen’s trawls as they were at dodging their traditional foes.

The two professors have co-authored an article about the topic in Nature Communications.

Their findings also show that there are far more of these fish in the sea than scientists previously knew. The scientists estimates that there are about ten billion tonnes of mesoplagic fish, up from about one billion tonnes.

The proteins are down there

Aksnes says that this is good news. Two reasons make these fish comprise a resource which eventually could be commercially exploited, he says. The first is that the amount of fish is enormous. The second is that they are low in the food chain.

The Norwegian professor thinks that our perceptions of what can be used to make fish feed, fish oils and fish products for human consumption need to change to ensure sustainable catches.

“We might have to fish stocks that are lower in the food chain to find sufficient seafood for the world’s growing human population. The enormous amounts of mesopelagic fish are an obvious choice,” says Aksnes.

If small fish never make it to our plates as tiny filets at home or at restaurants, there are other areas where they will be of use.

“They don’t comprise a dinner dish as they are, but the fish proteins are there. Proteins are filling, and that’s the main concern, not what the fish look like.”

Fish feed

He points out that aquaculture currently uses loads of feeds that are made from plants. Small mesopelagic fish can be a good solution for increasing the quantities of fish in such feeds.

“Small deep water fish can become important industrial fish,” says Aksnes.

However, a couple of factors count against them. They are tiny, so individual fish contain little meat. Another problem is simply catching them.

“We’ve yet to develop methods of catching them. So as of now commercial fishing would be unprofitable,” says Aksnes.

Impact on the oceanic carbon trap

Scientists have experimented catching Mueller’s bristle-mouth fish in Icelandic waters since 2008. The catch has varied from 46,000 tonnes in 2009 to 18,000 tonnes in 2010, according to the periodical Kystmagasinet.

Icelandic researchers have recommended a maximum quota of 30,000 tonnes because not enough is known about this fish and its proliferation.

Aksnes points out that scientists are also insufficiently clued in on the species’ importance for ecosystems. It is conceivable that other species would suffer if mesopelagic fish were extensively fished.

The oceans’ ability to capture atmospheric carbon dioxide could also be affected, at least to a degree.

“These fish have a certain impact, as they swim up at night, find food and start their day by diving to the depths when the sun comes up for us. This migration of nearly 1,000 metres a day represents the largest animal transport on the planet today,” he says.

“Because they take carbon with them into the depths, they contribute to the carbon cycle. The sea can thus absorb a little more CO2. But we need to research this more before we can specify what importance this really has,” says Aksnes.

Nonetheless, Aksnes predicts the small mesopelagic fish will be more in the limelight in years to come.

“Of this I’m quite certain,” he says.

-----------------------------

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no

Translated by: Glenn Ostling

Scientific links

- Xabier Irigoien, et.al: Large Mesopelagic Fishes Biomass and Trophic Efficiency in the Open Ocean. Nature communications, 2014.

- Stein Kaartvedt, Arved Staby og Dag L. Aksnes. Efficient trawl avoidance by mesopelagic fishes causes large underestimation of their biomass. Marine Ecology Progress Series. Vol. 456: 1–6, 2012 doi: 10.3354/meps09785