Larger offspring when fish pick own mates

It might not be so advantageous for us to help endangered animal species by selecting what we consider suitable mates for them.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

The number of species dying out on our planet is rising steadily. Around 56,000 animal and plant species are now red-listed according to the World Wildlife Fund.

One of method used to bolster populations of endangered animal species is to mate them with a partner we have found some distance away.

This helps propagate genetic diversity and is a safeguard against inbreeding and the risks that entails for weaknesses and diseases.

However, a new Norwegian study raises questions as to whether this is such a good idea.

Bigger offspring

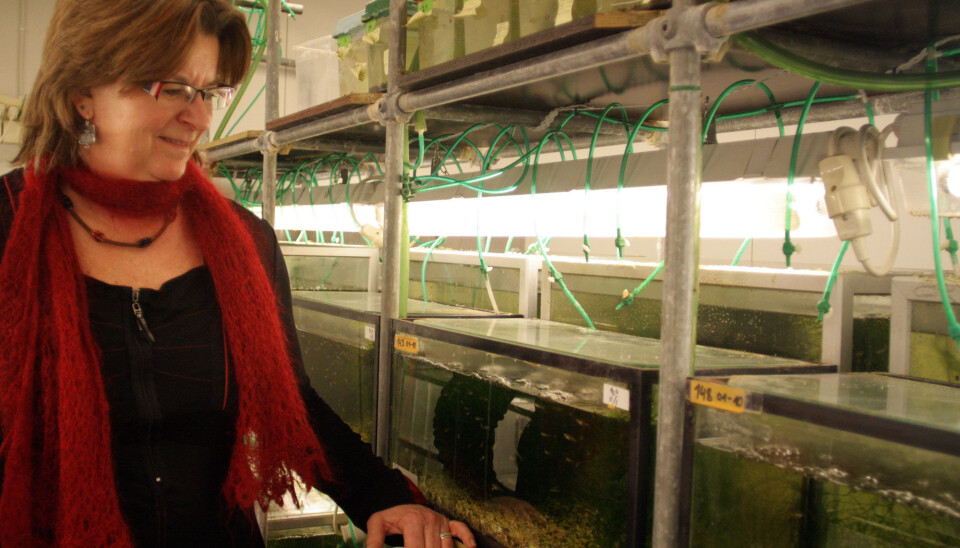

“We saw that the guppies that chose mates themselves had larger offspring than those that had been given a fish to mate with,” says Gunilla Rosenqvist.

She is a professor at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU)’s Department of Biology.

The researchers used guppies, as of course red-listed animals cannot be subjected to such controlled tests.

Another advantage of guppies is their relative short lifespans.

“They become sexually mature in just three months,” explains Rosenquist.

This enabled the researchers to study the biological impacts of choice of mates among the fish in twelve generations.

Arranged guppy marriages

As is the case with endangered species that are held in captivity and being helped to mate, the NTNU scientists found genetically differentiated partners for the fish in one study group. But these were not given a bunch of choices.

“We only gave these fish one partner,” says Rosenqvist.

The other group was allowed to share an aquarium with many of their species, ten females and ten males. They could select their own mates at will.

Like other animals, humans have subconscious biological instincts and drives that attract us to partners that are biologically preferable.

But what it is about any given pair of animals that make them optimal mates is often a mystery. It would be an advantage to know this when we are picking mates for an endangered species.

When Rosenqvist selected partners for the guppies their offspring turned out to be smaller in size.

“We know that in nature it’s advantageous to be big,” she says.

In many breeding projects for endangered animal species the goal is to set the animals or at least their offspring loose in the wild.

“Here in our study the fish live safely and have no competition for food supplies or enemies that can kill them,” says Rosenqvist.

The smaller sized fish might not stand a chance of survival out in open waters.

Genes, or no genes

It’s a far cry from guppies to pandas, but Rosenqvist thinks the results of her study can be applied to land animals.

Some of today’s endangered species now require human help to find a partner, and the variations in their genes have advantages.

“So we think it’s smart to mate them according to genetic diversity, but we have to weigh the pros and cons when we see this can lead to physiological changes,” says the biologist.

Several of the results from the breeding tests have yet to be analysed, including a change in colour witnessed by the researchers:

“After 12 generations the fish with a higher degree of genetic inbreeding are less orange in colour.”

“We’re continuing to analyse the results and one of the issues we’ll look into is whether sexual competition has an effect on colouring,” says Rosenqvist.

-------------------------

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no

Translated by: Glenn Ostling