Calves aren’t being given enough milk

Calves are subjected to a feeding regimen that is much too harsh, according to animal husbandry researchers. When allowed to drink as much as they wish the animals get healthier, happier and will yield more meat and milk.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

According to textbooks, calves cannot tolerate more than two litres of milk at a time.

But research shows the stomach of a calf has a volume of over five litres – more than twice what dairy farmers and agronomists thought possible.

Recommendations have been utterly wrong.

“Our research shows that calves can drink more than two litres of milk per meal without any risk of leaks to the paunch,” says Kristian Ellingsen, a researcher at the Norwegian Veterinary Institute and the leader of a recently completed research project.

Textbooks got it wrong

This is being described as a minor revolution in the trade and is good news for calves as well as dairy farmers.

The researchers found that calves are getting insufficiently fed with each meal, and the recommended total of six litres of milk per day is also too skimpy.

“Suckling calves on dairy farms start getting more milk as a result of this research. In my opinion calves are being grossly underfed if they only are given six litres per day,” says Ann Margaret

Grøndahl, a researcher at the Norwegian University of Life Sciences (NMBU). She has studied calves which are suckled by their mother cows.

As a consequence of skimping on milk, calves get sick, grow poorly and eventually become poorer milk producers.

“Several studies have shown that calves that drink as much as they wish are healthier, require fewer visits from vets, produce ten percent more milk as adults and show more rapid growth than calves forced to follow the recommended feeding regimen. In addition, dairy farmers can work less because they can cut down on the amount of times per day the calves are fed,” says Ellingsen.

Drank twice as much

This problem is international. Dairy farmers the world over have been following the same advice of limiting calves to six litres of milk per day, preferably in the course of two to three feedings.

The given explanation has been that excess milk can flow out of the stomach and over into the paunch – the rumen – which is the first chamber of a ruminant animal’s multi-stomached alimentary canal. A calf is born with an oesophageal groove with muscular folds that makes the milk bypass the rumen and go straight to its true stomach, called the abomasum. Milk in the paunch can essentially rot, rather than ferment like grasses or grains would. The result is diarrhoea and stunted growth. According to textbooks this occurs because the abomasum can only handle two or three litres of milk.

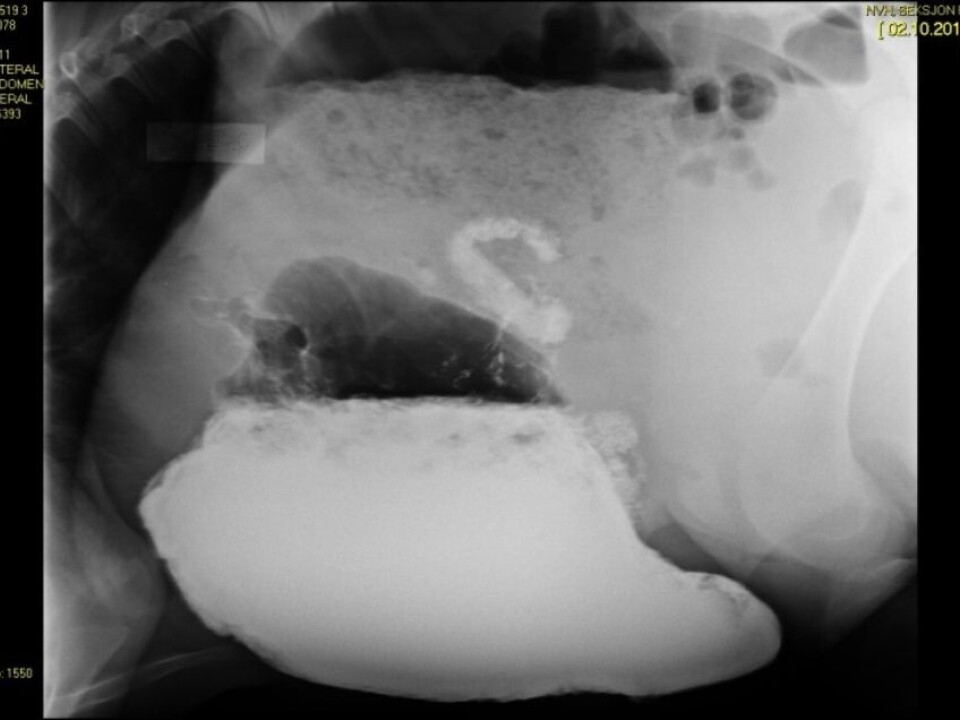

Ellingsen and his colleagues took x-rays to show that the abomasum is actually quite flexible and expansive.

The researchers gave six calves, aged three to four weeks, milk containing a contrast medium, and x-rayed their stomachs before, during and after intake to see where it ended up. Four of the six calves drank more than five litres and one calf drank a whopping 6.8 litres in one feeding.

“We saw that when the calves were allowed to drink their fill they were content to drink two to three times the recommended amounts without any milk spilling into the paunch,” explains Ellingsen.

Happier animals

Nor did the researchers observe any signs of bellyaches among these calves in the hours following these feedings.

On the contrary, international studies show that calves which are allowed to drink their fill are happier and livelier.

“We see this because the calves play more. Happy calves jump around, run, bow and butt with their heads,” explains Ellingsen.

He emphasises that the calves in the tests were fed milk from special containers with nipples attached. This limited the speed at which they drank while satisfying their need to suckle.

“If the calves have been fed with a bucket or a nipple with a large opening the results might have been different. This could explain the origin of this adage that calves shouldn’t drink too much.”

It used to be common for calves to drink milk directly from buckets placed on the floor. They guzzled this milk down so quickly that some might have spilled into the paunch.

A mystery

In any case, the researchers hope the new study will alter standard practice and that the textbooks will be revised.

“Allowing a calf to drink more milk is really positive and nobody needs to be concerned,” says Ellingsen.

“But this is conditional to their drinking through nipples which limit the flow and speed of consumption.”

How the myth got established about calves’ inability to drink their fill of milk remains a mystery.

“Perhaps it links to a wish to motivate calves to eat course fodder and feed concentrates earlier, and thus hasten them into becoming ruminants. But there is no need to push for such an early development,” says Ellingsen.

Another explanation is a concern that the calf would suffer rumen rot and diarrhoea.

“But rumen rot is not just caused by milk, and according to veterinary literature diarrhoea problems can be as readily caused by poor hygiene. Calves that drink a lot of milk do get a thinner stool. But this is not diarrhoea,” he points out.

“Stepchild in the barn”

Ellingsen also thinks some farmers don’t reflect enough on the way they raise calves. As there is no concern about immediate benefits, some don’t do enough to ensure that these newcomers in the barn are content.

“The calf is often treated like the proverbial stepchild in the barn. Many are placed in tiny pens with poor air circulation, which in turn leads to respiratory ailments and disease. I believe a lot of farmers don’t think sufficiently long-term,” says Ellingsen. “Good treatment of the heifer is essential for it becoming a good milk cow,” he adds.

To date the researchers have not received much opposition when presenting their results to the dairy trade.

“People have lots of questions. But it’s hard to refute the pictures,” he says, pointing to the x-rays.

FACTS

- In Norway, farmers are advised to give their calves about six litres of milk per day. In some countries the recommendations are down round four litres.

- During the first weeks of their lives, a calf is functionally monogastric, or simple-stomached. This is when milk is its main source of nutrition.

- Research shows that calves that get free access to milk through buckets or large bottles fitted with nipples drink about eight to ten litres per day. Calves that are allowed to suckle drink as much as 12 litres of milk per day at an age of two weeks.

- New-born calves eat hardly any solid foods for the first two or three weeks. As the gastrointestinal tracts in such young calves are not sufficiently developed to digest solid foods, a suckling calf cannot compensate insufficient amounts of milk by eating fodder or feed concentrates. This means that restrictive feeding with milk in the first three or four weeks leads to undernourishment.

Source: The Norwegian Veterinary Institute and the Health Service for Cattle/Tine Counselling

——————

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no

Translated by: Glenn Ostling