Young people make the least money on stocks

Old rich folks make the most money in the stock market. If you’re young and not particularly wealthy, then you’re more likely to lose money in the long run.

Researchers call this socio-demographics.

Two socio-demographic characteristics in particular – your age and your wealth – prove crucial for whether you managed to make good money on the Oslo Stock Exchange in the last 20 years, according to a new Norwegian study.

Financial researchers have previously found that the rich and experienced investors are those who over time make the most money on shares by far.

The researchers conducted the new study from the Oslo Stock Exchange with data and new methods that give them even more confidence in the results’ validity.

Young people flock to stock market

Figures from the non-profit foundation AksjeNorge show that more young small investors have entered the stock market in the past year than ever before. In March 2021, the Oslo Stock Exchange passed the half million mark for shareholders for the first time. As many as 40 percent of all new shareholders in the last three months are under 30 years old. And approximately 40 percent of shareholders have only invested in one stock.

Compared with pre-pandemic times, more than 130 000 new private individuals have started trading on the Oslo Stock Exchange

The media constantly reports on young people and students who have doubled or tripled their money through bold stock purchases in companies such as Kahoot, NEL, Gamestop and Tesla.

When the coronavirus hit us in March a year ago, the Oslo Stock Exchange crashed. But the COVID-19 decline was quickly turned into a stock market party.

Many people have made money on the stock exchange in the last year, especially a lot of young people.

Two researchers at BI Norwegian Business School share their thoughts about young people now flocking to the Oslo Stock Exchange and other international stock markets.

Experience is key

Samuli Knüpfer is a professor at BI and one of the researchers behind the new study of developments on the Oslo Stock Exchange. He sees a lot of positives in young people buying stocks.

“It’s good that more people – and especially young people – are interested in stocks and mutual funds,” says Knüpfer.

At the same time, the financial researcher is far from convinced that all these young investors will make good investments. Knüpfer and his colleagues see from their study that stock market success has a lot to do with experience.

“These are new investors who have little experience with how wrong things can go on the stock exchange. Some of them experienced the stock market decline in March last year, but it didn’t turn into a stock market crash and quickly recovered.”

A lot of people get burned

Knüpfer notes that sharp stock market declines are a reality that happens at fairly regular intervals. This is when investors really lose money.

“I’m afraid that a lot of people who’ve now made money on the stock exchange have a slightly overly rosy perception of what the future will bring,” he says.

“A lot of them could get burned.”

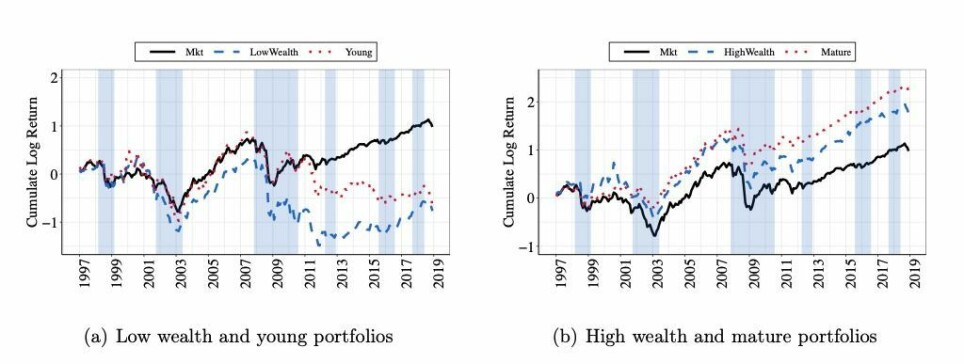

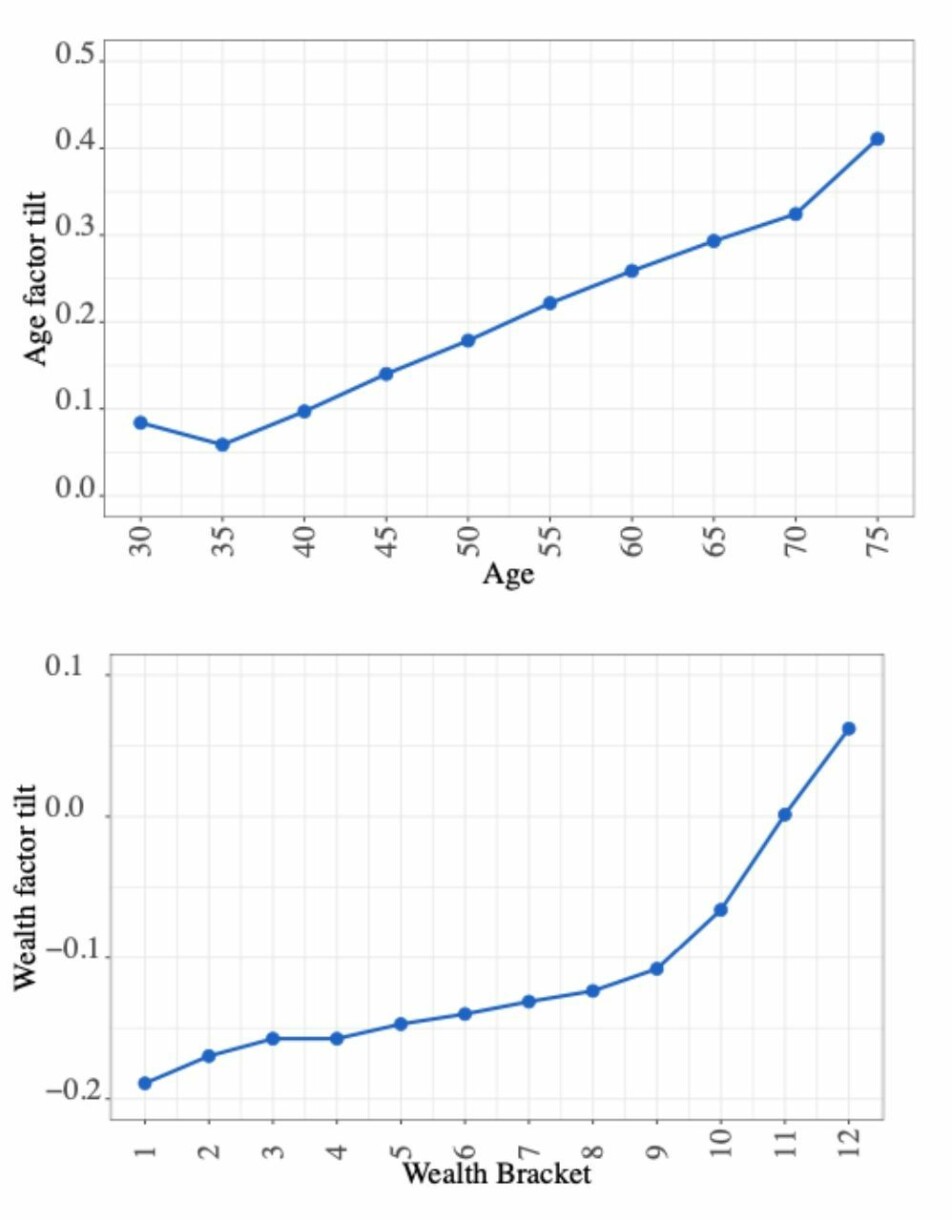

In the new study, Knüpfer and three research colleagues took a closer look at the socio-demographic characteristics of different types of investors in the Oslo Stock Exchange in the years 1997-2018.

Who made money and who lost money?

“We found that mature adult investors make the best investments in the long run,” says the BI researcher.

“Over time, stock purchases made by adults and experienced investors with greater wealth yield the most profit,” Knüpfer says.

Shares owned by mature and wealthy shareholders provide significantly higher returns over time than shares owned by other investors.

Researchers see the least return on equity portfolios owned by young and less wealthy investors.

Rich and old – a recipe for success

Knüpfer is a little worried that the large investment returns that many young adults received on growth stocks in recent months will encourage even more young people to invest narrowly and boldly in the stock market.

Knüpfer and his colleagues found the same pattern on the Oslo Stock Exchange as other financial researchers have found in similar earlier studies. At the same time, better data and better research methods increase the researchers’ confidence in what they see.

What do older and younger investors do differently?

Knüpfer points to poorly diversified equity portfolios as the main reason why young and less affluent shareholders see the least return in the long run.

Diversifying the equity portfolio means spreading the risk you take. You do this by buying several diverse sto ks.

If you own shares in only one, two or three companies, then you’re living dangerously if you’ve invested a lot of or all your money in them. If you instead own ten fairly different stocks, the risk you take will be less. If you own a hundred different stocks, the risk will be even smaller.

Equity funds spread risk

Paul Ehling is also a finance professor at BI. He completely agrees with Knüpfer advice on how important it is to diversify the equity portfolio.

“Everyone who deals in finance knows this. This is also the advice you’ll get if you go and talk to a financial adviser at a bank,” he says

“This is also the reason why beginners in the stock market should invest in equity funds, and perhaps most preferably index funds,” says Ehling.

If you invest your money in an equity fund, the money is spread over many different stocks. You get a well-diversified equity portfolio. If you invest in what’s called an index fund, the fund will simply mirror the price development on the stock exchange. Index funds are also much cheaper than other equity funds.

Experience and knowledge

Ehling believes that the results of the study by Knüpfer and his colleagues that are attributed to differences between age groups and between more or less wealthy people, are actually largely about experience and knowledge.

He notes that investing in stocks is something that is also inherited to a great extent.

“If you had a father who owned several stocks, then chances are good that you’ll own stocks too. There’s also a greater chance that you’ll make money on your investments,” says Ehling. He points out that most rich people are stockholders.

“But if you’re the first in your family to own stocks, you more often tend to take too great a risk or you have an equity portfolio that isn’t diversified enough.”

You have to get paid for risk

Ehling points out that how much risk you take is absolutely crucial.

“If you invest your money in risky stocks or stocks that fluctuate a lot in value, then financial theory says that you can expect to receive a certain risk premium compared to putting your money into less risky investments,” he says.

So you get paid to take risks – you really have to, if there’s to be any point in taking those risks. And in the long run, this may not be the smartest thing to do. This is an area where research points in different directions.

Ehling also notes that the risk premium you receive is reduced as the share prices rise on the stock exchange. In other words, the premium goes down the closer the prices get to a possible peak.

“If you have experience in stock trading, then this is something you already know. That’s why the rich and prosperous take fewer risks when they sense that equity values are beginning to approach a peak. Then they invest their money in safe companies that are often referred to as value stocks,” he says.

How many different stocks should you own?

“Investing in the stock market isn’t rocket science,” Ehling points out.

“There’s a lot of available knowledge out there for people who start looking.”

But the crucial knowledge Ehling believes you need is to diversify your investments. You shouldn’t invest too narrowly.

If you choose to put your money into individual stocks instead of purchasing equity funds, there is a lot of research on how many different stocks you need to achieve sufficient diversification.

This study of stock ownership on the Oslo Stock Exchange, conducted by Professor Bernt Arne Ødegaard at the University of Stavanger, states – as do several other studies – that you’ve managed things well if you distribute your investments among ten different stocks.

“If you gamble on the stock exchange by only owning three to four different stocks, in my opinion you’re taking an almost ridiculously large risk,” says Ehling.

In Ehling's opinion, ten different stocks is still too small.

“Even thirty different stocks is too small if you want to achieve good diversification. Experience would suggest that inexperienced investors who don’t spend much time following the stock market should focus on investing in equity funds,” he says.

Translated by Ingrid Nuse.

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no.

Reference and sources:

Sebastien Betermier, Laurent Calvet, Samuli Knüpfer and Jens Kvaerner: "What do the portfolios of individual investors reveal about the cross-section of equity returns?", SSRN, March 2021. Summary.

The non-profit foundation AksjeNorge and the business newspaper Dagens Næringsliv (DN).

The research we write about here is partly funded by Finansmarkedsfondet. Forskning.no / ScienceNorway.no has also received support from Finansmarkedsfondet to write about economics and finance, but with full editorial freedom.