Girls are given less ADHD medication

Boys are much more frequently prescribed drugs against ADHD than girls. As it’s often construed as a male malady, there could be a tendency to underdiagnose the disorder among girls.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

This has been made evident in a study published by the Norwegian Medical Association’s journal.

Researchers at the University of Bergen have studied prescription rates for ADHD drugs from 2004-2008, including the amounts prescribed and data on the recipients.

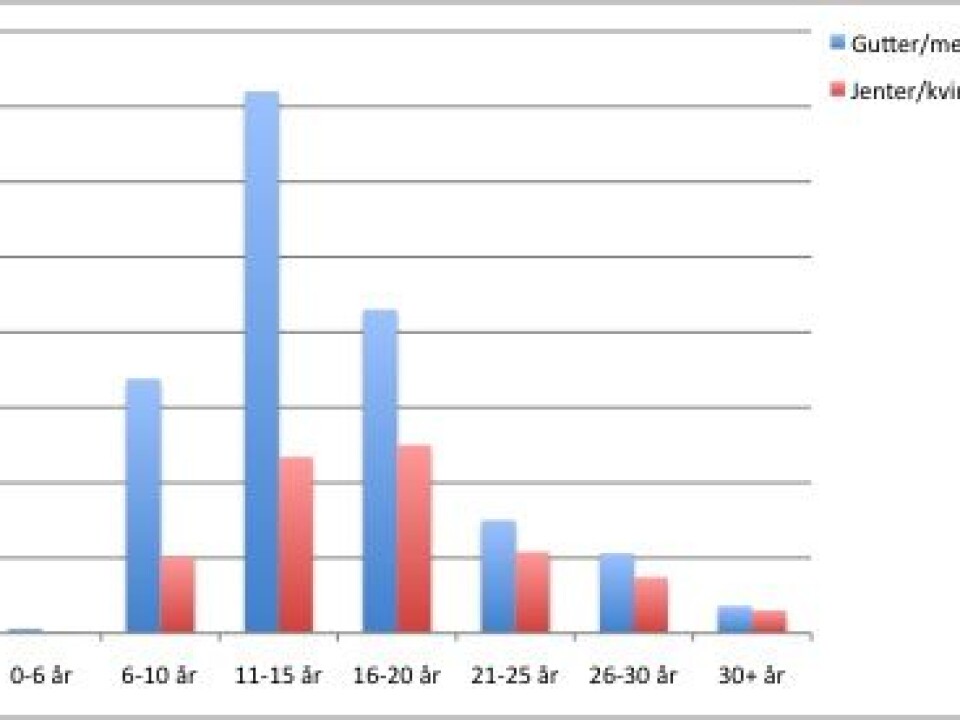

While 3.6 percent of boys aged 11-15 were found to be collecting prescriptions against ADHD in 2008, the share of girls getting such drugs was 1.2 percent.

“We find that more boys are getting the drugs than girls,” says Sabine Ruths, a professor at the University of Bergen’s Department of Public Health and Primary Health Care.

“But we don’t know if it’s because more boys have ADHD or it’s because the diagnosis isn’t given often enough to girls.”

Later peak for girls

Approximately 3-5 percent of Norwegian children and adolescents have some form of ADHD. This is a varied diagnosis, with symptoms ranging from moderate concentration problems to real trouble sitting still at all.

It is assumed that more boys than girls have ADHD and this can explain some of the difference between the sexes.

But Ruths says some of the findings in the study point in another direction:

“We see that boys reach their peak in medication around the age of 13, whereas girls peak at the age of 17.”

“This could mean they start medical treatment too late, when they have already completed their compulsory education. Perhaps there should be much more focus on girls,” she says.

Gender difference levels off with age

Researchers suspect that sometimes ADHD among younger girls is misdiagnosed as learning difficulties or other emotional problems. But the mistake is being rectified:

“The gender difference has been decreasing over the years. In 2004 nearly four times as many boys were prescribed the drugs, but in 2008 their number was just double that of girls,” says Ruths.

“We think the decrease can be attributed to a general focus on ADHD – parents, teachers and health personnel have become more attentive to the fact that this is rather common among girls too.”

The gender difference among patients who take the drugs in their twenties is nearly negligible.

“This gives us reason to believe that girls who start using the medicine are more likely to continue the treatment into adulthood, whereas more boys quit by their teens. Boys could also be over-treated or girls could be under-treated. We don’t have sufficient diagnostic material to determine that,” she says.

Family doctors take over, but need help

An ADHD diagnosis can only be made in Norway by specialists, for instance a child psychiatrist. But once the diagnosis is made, the family GP takes over from the specialist health services.

They shoulder this burden more and more:

Whereas just 17 percent of the prescriptions for ADHD drugs were written by family doctors in 2004, the share had grown to nearly half – 48 percent – just four years later.

Ruths thinks we should really take note of this development:

“Apparently there’s a tendency in the health services to transfer an increasing load of tasks from the specialist health services onto the shoulders of family doctors. But the family doctors have to do a hundred other things and cannot be specialists in every field,” says the professor.

“So it’s important for the specialist health services to follow up the patient, for instance through annual check-ups or when a need to consider adjustments in treatment is perceived. It’s essential to enable family doctors to quickly refer the patients to specialists when their help is required. Smooth cooperation is needed among the various elements of the public health services.”

Is such cooperation sufficient now?

“It’s good in some areas, but in others improvements are called for, for instance in psychiatry.”

----------------------------------

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no

Translated by: Glenn Ostling