Economist wins the Nils Klim Prize

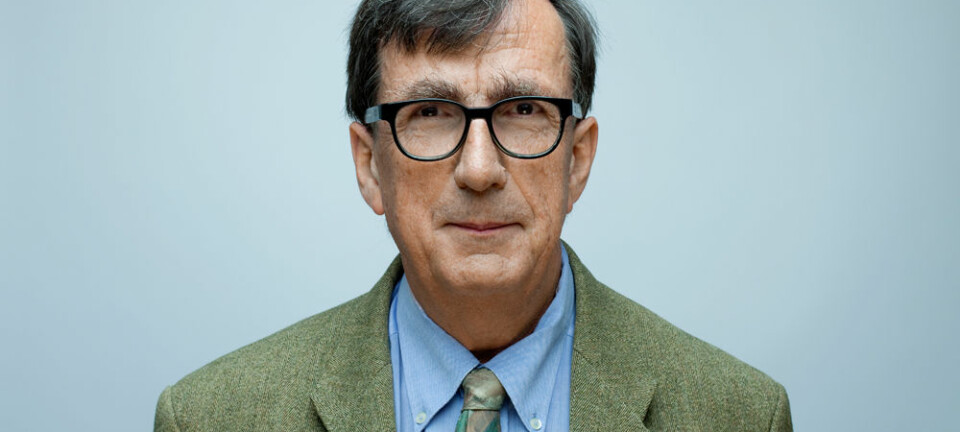

Ingvild Almås of the Norwegian School of Economics (NHH) has been awarded the Nils Klim Prize for researchers under the age of 35. “A terrific inspiration,” she says.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

“I think these kinds of prizes are important in general. But I think they’re particularly important for motivating young researchers,” Almås says.

She was not present at the Student Culture House in Bergen when the announcement was made this week. The award ceremony will be at Håkonshallen in Bergen on 5 June.

“I spend quite a bit of time alone and occasionally have to struggle to get funding for our projects. It’s wonderful to get this recognition, because it show that what we’ve done so far meets expectations.”

The 34-year-old economist from the Norwegian School of Economics in Bergen is rather modest in her self-appraisal.

The jury that awarded the Nils Klim Prize points out that Almås has published research at the highest international level and describes her as an exceptionally gifted researcher.

Weaknesses in gauging gaps between rich and poor

Almås has investigated perceptions of economic justice and revealed weaknesses in existing methods for measuring the differences between poor and rich countries.

“I’ve focused on how we should compare incomes across national boundaries and the mistakes we make in the traditional methods used, for instance, by the World Bank and the UN,” says Almås.

That research has shown that current methods give unreliable, divergent results and thus that global inequalities are underestimated.

Almås asserts that a clearer picture of the disparities between poor and rich countries is attained by studying what food their residents have actually grown and bought, rather than using something called exchange rate-based measures to make comparisons.

“The poorer the country, the more evident it is that traditional methods overestimate the country’s income. I have identified a systematic effect that leads to underestimates of global inequalities, as seen in the World Bank’s and the UN’s assessments, for example,” says Almås.

Fairness research

Almås has also worked with normative issues that bridge economy and philosophy.

She has studied the inequalities that people view as just and the fairness of the distribution of income in Norway.

Almås has shown that the perception of fairness changes dramatically in the course of adolescence. Most 10-year-olds support an even distribution of wealth.

“But then something happens at around the age of 12. They start to be concerned about who has earned the wealth and more start supporting the notion of distribution according to efforts and abilities,” says Almås.

“Most of the oldest children are meritocrats. They regard equal distribution as unfair and think it’s right to distribute weath in accordance with how much work someone does. They are not as supportive of egalitarian principles,” says Almås.

Another important aspect of this research is the distinction between unequal incomes and unfairness.

“We’ve shown that although the inequality of incomes in Norway has diminished slightly in recent decades, it looks like we’ve moved toward a more unfair society.”

Role of social science

Almås has no doubts that social science still can play an essential role in the development of society. She cites schools as an example.

“Before implementing a new reform the effects of earlier reforms need to be charted and we have to have the cards on the table concerng the causes of disparities in schools and later in life. We also need to know what results in top-notch achievements.”

She points out that social science can reveal causalities that can enlighten politicians and other decision-makers.

“In a rich country like Norway we can afford to come up with good social solutions and thus we should also have the means to finance research that enables us to implement them,” she says.

Translated by: Glenn Ostling