This article is produced and financed by University of Oslo - read more

Rigid treatments could lead to more drug-resistant tuberculosis

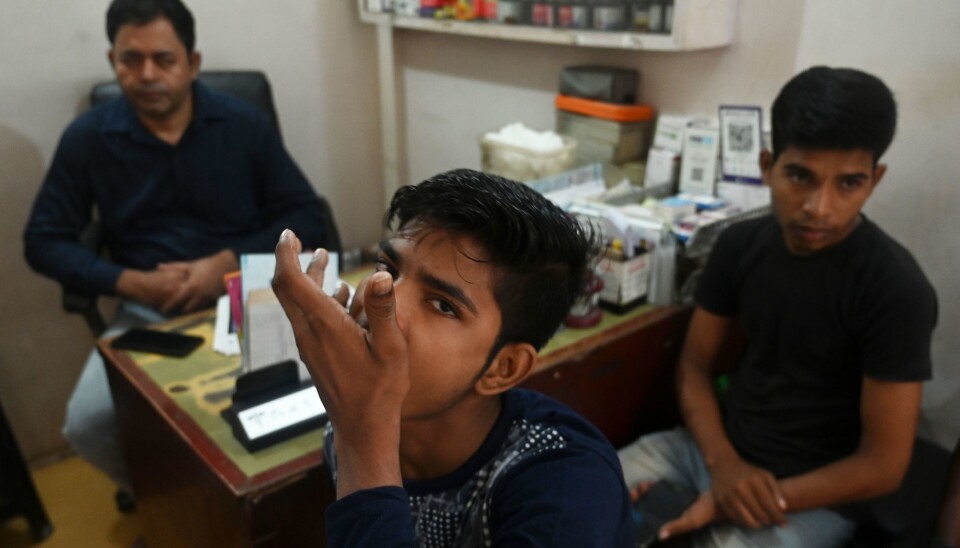

To ensure patients take their pills, the WHO recommends that health care personnel watch them being swallowed. If this method is implemented in a rigid way, it may lead to the emergence of more drug-resistant tuberculosis instead of less, according to a new study.

Around 10 million people worldwide fall ill from tuberculosis every year and 1.6 million people die of it. Particularly burdened by the disease are the sub-Saharan African countries.

The WHO has an ambitious strategy of a world free of tuberculosis deaths by 2035. Direct observation of drug swallowing, a treatment known as direct observation therapy (DOT), is a strategy developed and recommended by the WHO to fight the problem of tuberculosis.

DOT is invented to increase adherence of tuberculosis patients, thereby preventing any possible complications such as the development of drug resistance. However, a qualitative study among health personnel in Ethiopia identifies a mismatch between the intentions behind the treatment and the lived reality.

“For a treatment to be effective, it needs to be context sensitive to the patients’ situation. If care is implemented without considering the world the person lives in, that increases the risk of patients failing to follow through on important treatments,” says Kirubel Manayzewal Mussie, lead author of a recently published study in BMJ.

Patient-centered treatment

Over a period of two months, Kirubel Mussie interviewed 18 healthcare workers in Ethiopia, all working with DOT as a treatment for patients ill with tuberculosis.

DOT means that healthcare personnel watch patients taking their medication, and the method is at the forefront of Ethiopia’s battle against tuberculosis.

All the healthcare workers interviewed mentioned the importance of understanding the patients’ situation in order to increase treatment effectiveness. The rigid implementation of DOT could lead to treatment fatigue among the patients, the healthcare workers observed.

“Treatment of drug-resistant tuberculosis is demanding for anyone. And when the disease affects people who are already struggling to make ends meet, who live far away from healthcare facilities and who usually lack the necessary health education, the treatment becomes extra demanding,” Kirubel Mussie Says.

It is crucial that people ill with tuberculosis follow through on their treatment in order to prevent the disease from spreading and developing resistance to antibiotics.

“The healthcare workers felt there was little to no flexibility to adapt the treatment to patients’ situation, for example giving patients drugs to take at their homes to ease the burden of daily travels to receive their treatment at the healthcare facilities. An overwhelming focus on pill-swallowing serves the opposite purpose. A patient-centered approach is necessary, and this should go beyond words.” Kirubel Mussie says.

Broader perspectives

Tuberculosis today is the leading cause of death in Africa, according to the WHO 2018 Global Tuberculosis Report. The African continent accounts for a quarter of all new cases.

Although the WHO indicates that sensitivity to patients needs and flexibility are integral parts of DOT practice, this does not comply with the practice of the treatment witnessed by some healthcare professionals in Ethiopia.

“This study shows that there is a need to embrace new perspectives in the treatment of drug-resistant tuberculosis and thereby enhance the practice of DOT among healthcare providers,” Kirubel Mussie says and emphasizes:

“More research, drawing perspectives from disciplines such as medical ethics, human rights and anthropology, could further explore the challenges of integrating and implementing DOT as a treatment for tuberculosis in fragile healthcare systems.”

Reference:

Kirubel Manyazewal Mussie, Bridging the gap between policy and practice: a qualitative analysis of providers’ field experiences tinkering with directly observed therapy in patients with drug-resistant tuberculosis in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, BMJ Open, May 2020