This article is produced and financed by University of Oslo - read more

Climbing route at Mount Everest becomes safer with satellite and tracking data

Satellite and tracking data can help provide a safer climbing route up the dangerous Khumbu Icefall of the world's highest mountain.

The highest mountain in the world – Mount Everest – has attracted high altitude climbers and explorers for decades. Climbing the mountain is dangerous, and when climbing from the Nepalese side, the challenges start right after leaving base camp, as one needs to climb the almost two kilometers long Khumbu Icefall.

A new method based on optical data from satellites estimates the velocity of the icefall. These estimates were verified with geographic tracking data from personal devices, volunteerly provided by climbers. These estimates can help in providing a safer route over the icefall, according to a study published in Journal of Glaciology by researchers from the University of Oslo.

The researchers found a way to extract the optical data taken by a satellite with a special multi-temporal technique. The new method gives a detailed velocity map of the Khumbu Icefall, something that had not been possible before.

Fast moving icefall

The Khumbu Icefall is a large and dangerous obstruction at the foot of Mount Everest. The icefall section is right outside base camp on the Nepalese side, and is an impressive section of the glacier with an almost 1000 metre high drop.

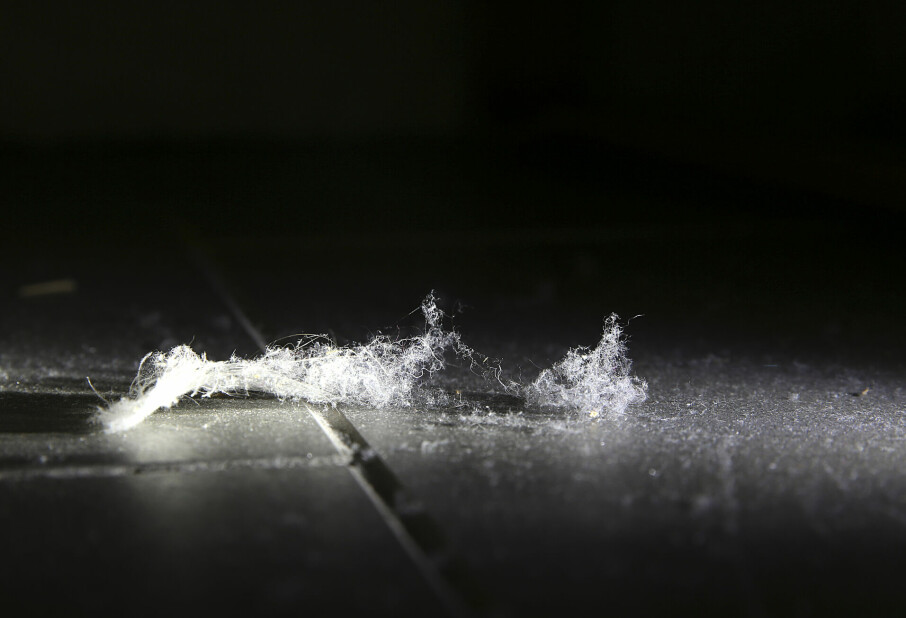

The icefall is where the glacier is funnelled through a narrow part of the massif with high granite flanks on both sides. The steeply descending ice is highly dynamic, causing sudden opening and closing of crevasses, and even collapse of “ice towers”.

To make a climbing route through the icefall, trained local Nepalese workers establish a route and stay in the base camp to maintain this trail throughout the season. The route is comprised of fixed ropes and ladders, making it a much faster passage for the high altitude mountaineers and guides.

Creating a velocity map of the icefall

The researchers wanted to estimate the velocity of the icefall. To put together a velocity map they used data from Sentinel-2, a European imaging satellite that records the whole Earth’s surface at least every five days. They needed a large collection of satellite images to get a velocity field with high resolution (30 meters). Their satellite estimates revealed velocities of at least 1 meter a day during the winter season.

The frequent passes of Sentinel-2 makes it possible to see the detailed flow of the ice in the icefall, which was not previously possible with other satellite systems because crevasses were opening and closing too quickly for the image sequences to follow, explains Bas Altena, lead author of the study. The first Sentinel satellite was put into orbit in June 2015, and Altena has estimated the velocity of the icefall for some years.

However, he had not been able to verify the velocity estimates, since there is no GPS instrumentation on the icefall. Altena had an idea: The route log and tracking apps used by athletes have positioning and time data.

If he could use such tracking data from climbers passing through the icefall along a route, and compare these with the satellite data, it would be possible to verify the velocity of the ice flow. After some emailing, he made contact with a Norwegian climbing team, one of whom was a PhD student at the University of Oslo.

The Norwegian Everest Expedition of 2019

The Norwegian climbing team with Didrik Dukefoss, Thomas Lone and Håkon Erlandsen made a successful ascent of Mount Everest in 2019. They had recorded their climbing with their private GPS devices, and they could give the researchers their geographic position data.

Didrik Dukefoss recalls his ascent:

"Passing through the Khumbu Icefall was both extremely exciting and quite terrifying. I almost had to pinch myself to grasp that the beautiful and dramatic surroundings were real. We mostly moved through the icefall during early hours as the temperature drop of at least 20°C from the day maximum stabilises the ice and makes the journey safer", he says.

"It was fascinating to observe the vast day-to-day changes in the enormous mass of ice. If the velocity maps may assist the “icefall doctors” in optimising the ever-changing icefall route and making their own job safer, that is of course great news."

Saving lives with knowledge and data

Climbing the Khumbu Icefall has been fatal for several people. An avalanche in 2014 killed 16 people, the same happened in 2009, killing another three people. All of these casualties were local Nepalese workers, guides or porters.

The researchers hope the velocity map can help the climbing community in making safer routes through the icefall. The maps can be used to reduce the time people need to be in the icefall, knowing where the ice flows fastest or where most crevasses open up.

The study also shows an example of new and surprising applications that satellite data can generate. With large volumes of remote sensing data in combination with other apps like GPS tracking data it is possible to create improved products and new insights.

Reference:

Bas Altena and Andreas Kääb: Ensemble matching of repeat satellite images applied to measure fast-changing ice flow, verified with mountain climber trajectories on Khumbu icefall, Mount Everest, Journal of Glaciology, 2020. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/jog.2020.66