An article from University of Oslo

Beware of the limitless joys of nature

If Norway does not set clearer limitations to the public access to land, we risk sawing off the branch we’re sitting on.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

Go out and climb trees, we tell our children, hoping that they’ll learn proper, motor skills and feel happy about being outdoors.

Norwegians are fond of taking long hikes in the mountains and skiing through snowy landscapes, but we are not alone in being outdoorsy in the North.

On January 1st, 2012, newly revised changes in the Outdoor Recreation Act came into force in Norway. The act ensures our ability to wander freely and enjoy nature around us without encountering too many fences or restrictions. But so what if we come across a few rules and regulations on our way?

Researcher Marianne Reusch is skeptic to a general expansion as an instrument to provide us with free access to beaches, forests, mountains and open spaces.

«Limitless joys»

"Simply put, I’m naming the public access to land “limitless joys". I believe this expression includes both the good of being able to travel around freely, but that it also contains an element of risk; a risk of overconsumption and too intensified usage of nature," Reusch sums up.

She has written her doctoral theses on the public access to land and the legal basis for the outdoor life in the North in general and Norway in particular, and defended her thesis on January 18 at the Faculty of Law at the University of Oslo.

The privileges may be undermined

"I am not convinced that expanding privileges favoring the public will protect and strengthen the public access to land in the long run. On the contrary, I believe that an uncritical expansion of privileges, together with lacking definitions and regulations, may lead to an undermining of these privileges," says Reusch.

She thinks that the Norwegian strategy, where we are so afraid of the introduction of limitations, is a bit dangerous.

"Maybe we’re about to cut off the branch we’re sitting on. Simply put, I think that the public access to land, or parts of it, must tolerate a few more limitations to have a chance of being viable in the long run," says Reusch.

To make sure this happens, she thinks it’s a good idea to look to our neighboring countries to see what they have done in this regard.

We share our problems

In international literature, the Scandinavian countries are portrayed as if equal rules of law exist all over, very often with a reference to Swedish law. But the laws of outdoor life in the North are a field without legal cooperation of any kind and with no objective of having legal consensus.

Different traditions exist among the countries as to how access to beaches, forests and mountains are regulated, in addition to their varying geography and dissimilar historical backgrounds. But in spite of these differences, the countries struggle with the same kind of problems.

"I believe the heart of the matter regarding the Nordic countries’ challenges with legislations and public use of nature is that our population has increased at the same time as natural areas shrink," says Reusch.

The Norwegian Outdoor Recreation Act is from 1957- since then the population has increased by over one million.

Commercializing nature

An example of challenges might be professional organizers who demand payment for allowing people to use organized natural areas. Another example is the situation where professionally organized hiking teams disturb hunting in landowner’s own woods and mountains.

"A challenge of today is that outdoor life is exploited in new ways and has become more commercialized. Mass excursions, altered ways of passage, and use of public access privileges in a commercialized way for other purposes than outdoor life, all rise questions with no straight answers", the researcher explains.

So why is it a big deal if some parts of our nature are used commercially?

Mountain hotels are examples of a long tradition of commercialized usage of the public access to land. But some forms of commercialized outdoor life replace ordinary outdoor life and are only inconveniencing the landowner, according to Reusch.

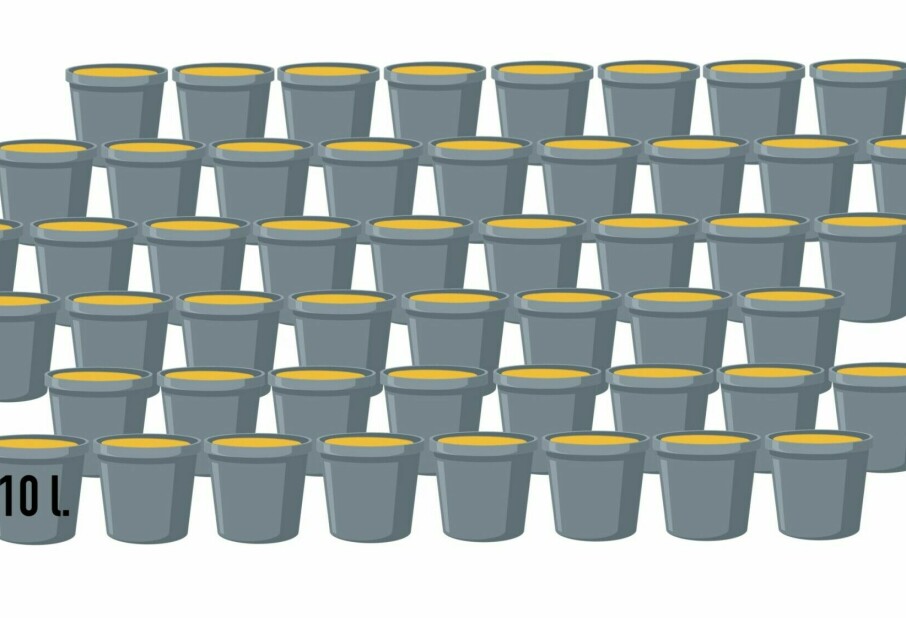

Sweden and Finland both have problems with busloads of berry pickers “invading” their forests. Commercial wirepullers may earn big money on this, while at the same time the landowner’s own trade is affected. When these buses of berry pickers arrive in Norway, they are met with rules dating 55 years back in time.

"Our regulations have only a certain standard for addressing such problems. Iceland, on the other hand, has faced these problems with their own set of rules on commercial outdoor life," says Reusch.

Learning from each other

"We may learn a lot by talking to each other. By studying our neighboring countries’ legislation, we are prepared with possible solutions to problems which have not yet arrived in Norway. A more clear distinction between the rights concerning traditional, down-to-basic outdoor life, and the rights concerning organized and commercial activities will be both necessary and reasonable, I believe. There are many other countries which seem to have found useful solutions to these questions", Reusch states.

When working on her dissertation, she discovered the high level of advancement that some countries’ legislations have regarding public access to land and the way they address these problems. There are also examples of the opposite.

"But the main impression of the international material is that there exist a whole set of rules which arranges outdoor life in a proper manner. Countries with a higher population and with tighter area resources are often way ahead of Norway with regards to the development of rules and solutions that pay respect to mass wanderings, and wear and tear of nature, and make nature accessible for the public at the same time. You need not travel far to find good examples of the latter," concludes Reusch.

--------------------------------------------------

Read the article in Norwegian at forskning.no