This article was produced and financed by Diku - The Norwegian Agency for International Cooperation and Quality Enhancement in Higher Education

Immigrant parents have different expectations of Norwegian kindergartens

Views on children, play and learning vary greatly between European countries. This also affects kindergarten staff in their day-to-day work, where they deal with children and parents of many different nationalities.

If your children have attended a kindergarten in the UK, Greece or Poland, your experience is sure to be different from that of parents who are only familiar with Norwegian kindergartens. And your attitudes to and expectations of a Norwegian kindergarten will be coloured by your experience.

The kindergarten teachers you meet will therefore benefit greatly from insight into how kindergartens are run in other countries.

"Attitudes and values are so different. There is so much behind parents’ thinking and decisions that we are not aware of," says Anne Elin Teigland, manager of Kidsa Øvsttun kindergarten in Bergen.

Learning about communication and cooperation

Teigland is coordinating a collaboration between kindergartens and organisations in five European countries aimed at improving kindergarten staff’s parental cooperation skills.

Among other things, a written guide will be produced. The guide will help kindergarten teachers to understand and communicate with parents and guardians in different family structures and from varied cultural backgrounds. The goal is to achieve good cooperation that is in the children’s best interests.

Greece, Croatia, Poland and the UK are taking part in the project as well as Norway. The project is funded by the Norwegian Centre for International Cooperation in Education (SIU) through the EU’s Erasmus+ programme.

"Through cooperation, we learn a lot about ourselves and who we are when dealing with others. There are so many different angles on how to best accommodate other people," says Teigland.

She believes it is important for kindergarten staff to be aware of how they speak to parents in different contexts: when bringing and picking up children, in parent-teacher talks and parent meetings. They must clarify expectations and explain their work methods.

Important to involve parents

Studies show that the cooperation between kindergarten staff and parents is important to children’s well-being, learning and development. Studies also show that kindergartens would benefit from involving parents more than they do at present. A good dialogue helps to boost parents’ trust in the kindergarten and their understanding of the values the kindergarten is based on.

Professor Elin Eriksen Ødegaard of Bergen University College is also attached to the project. She has been engaged in research on teaching in kindergartens for many years and believes that kindergarten staff must take a holistic approach to the environment children are brought up in.

"They have to take an interest in the children’s lives outside the confines of the kindergarten and make the families participants in the children’s education in the broadest sense," she says.

For families who have recently moved to an area or who for other reasons do not have a big network, the kindergarten has an especially important role to play in building a robust network around the children.

Superficial cooperation

The Norwegian Kindergarten Act states that kindergartens shall work in close understanding and collaboration with the children's homes. Ødegaard believes, however, that this collaboration is often too superficial.

"We need to develop our teaching in relation to parental cooperation. A lot of psychological knowledge underlies how kindergartens presently endeavour to create a sense of attachment and security for parents and children. We need to retain that, at the same time as we need to strengthen the cultural perspective," she says.

Ødegaard believes that today’s multicultural society makes it necessary to change the current political framework’s model for what a kindergarten teacher should be. She recently chaired a national working group that submitted a draft revised framework plan for kindergartens.

The Ministry of Education and Research has distributed the proposed framework plan for consultation with a view to implementing it from autumn 2017.

Big differences between countries

Linn Vatnedal is one of three educational supervisors at Kidsa Øvsttun kindergarten who are part of the project group together with Anne Elin Teigland.

Vatnedal says that there are big differences in how kindergartens function in the five countries, and in how parents view kindergarten staff. In some of the countries, the prevailing attitude is that kindergarten teachers are the experts and know best what the children need.

"Here, we are used to closer cooperation between the kindergarten and the home, and to jointly finding the best path for each individual child," Vatnedal says.

One of the goals of the project is to include and motivate parents to become more engaged in day-to-day activities in the kindergarten.

People’s views on children and learning also vary. In Norway, people believe that children should be seen, listened to and understood, that children are active participants in their own educational process. That is not the case everywhere.

Can lose their job because of a sick child

Cultural differences make great demands on kindergarten teachers’ communication and cooperation skills, Vatnedal believes.

"When we see how they work in other countries, we understand better why some of these parents react as they do. They are used to a completely different system," she says.

Her colleague Ina N. B. Juell tells about an illuminating experience she had on a study trip a few years ago. The manager of a kindergarten she visited with her colleagues explained the consequences it can have for a family if a child has to stay at home because it is ill.

"Their pay can be docked, and they can lose their job if it happens several times. We don’t think in those terms here, where we have a good welfare system that provides security if anything happens. Conditions like that also affect children’s everyday lives," Juell says.

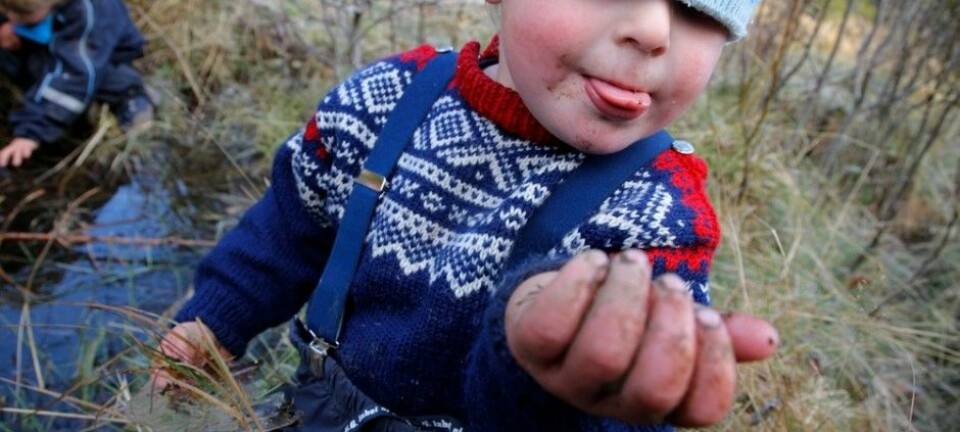

Letting the kids get dirty

Kidsa Øvsttun is a nature kindergarten that emphasises outdoor activities. Some of the children who come here have never worn waterproof clothes before. And suddenly they have to be outdoors in all kinds of weather, in a city renowned for its plentiful rainfall.

It soon becomes very apparent that key concepts such as outdoor pursuits and risky play can have very different content depending on where you are in the world. And that it is important to inform the parents about how the kindergarten works.

"A common attitude in Norway is that the dirtier the children are when they go home, the more they have played and the better they have enjoyed their day at kindergarten. But some people find that really terrible," says Jannicke Sagosen.

She says that the different ways of viewing children also affect the work methods employed in the different countries.

"In Norway, we are concerned with children being unique individuals who each think in different ways. In some other countries, the system is more adult-controlled, and the children have less opportunity to influence what their day is like. In that kind of system, it’s easy to get hung up on the product – that children make nice drawings, for example – than what they learn from the process," says Sagosen.

An open educational set-up

Given such different points of departure, collaboration on the project is a challenge in itself. Cultural and language barriers meant that the participants initially had to spend a lot of time arriving at a shared understanding of the goal for the project.

Now they are well under way, however, and the project will continue until summer 2018.

The work will result in a set of methods and teaching material that the participants will take back with them to their respective organisations and use to guide colleagues. The teaching methods and material will also be made available to other kindergartens, organisations and educational institutions.