An article from KILDEN Information and News About Gender Research in Norway

Failed campaigns against female genital mutilation

International organisations that campaign against female genital mutilation are being met with scepticism. Changes must come from within, says researcher.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

Despite years of heavy investment, female genital mutilation (FGM) has major support in countries such as Somalia and Ethiopia.

“People have tried to fight this custom in Somalia for more than 30 years. We have to realise that it has been a failure”, says Abdi Ali Gele at Norwegian Center for Minority Health Research (NAKMI) in Oslo.

Study on attitudes

Gele has studied attitudes towards FGM among Somalis in Oslo and in the districts Hargeisa and Galka'ayo in Northern and Central Somalia.

Whereas only 30 percent of the informants in Oslo were in favour of FGM, the same applied to 90 percent of the informants in Somalia.

Similar studies have not been carried out since the 1980s and 90s. Then 90 percent of Somali women said they wanted the custom to continue.

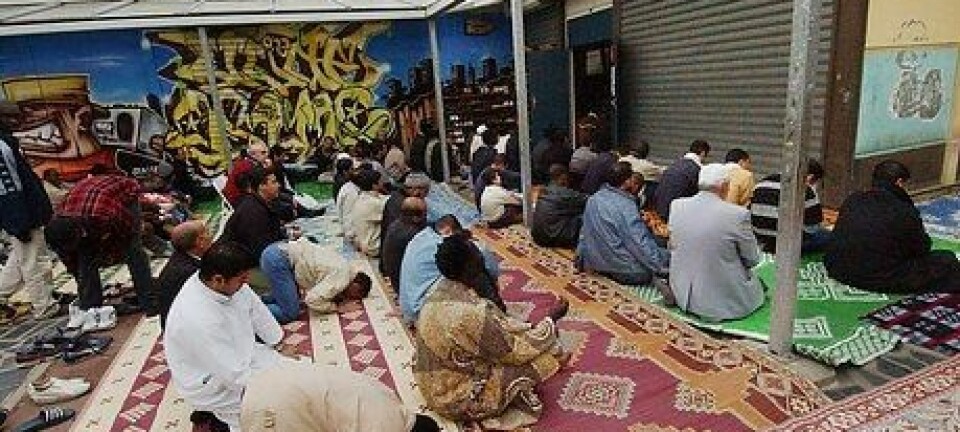

“In Somalia, people are sceptic towards the programs which are working for a zero tolerance policy towards FGM. These programs are administered by organisations which come from outside. The message is forced upon them. People interpret it as if the organisations want to alter their values and their religion,” says Gele, who came from Somalia to Norway in 2003.

Strong traditions

FGM has been a custom in Somalia for centuries. 28 African countries share the tradition, but nowhere in the world is the custom more widespread than in Somalia.

The first campaigns against FMG in Somalia were initiated by the previous Somali regime in the beginning of the 1970s. These efforts collapsed, however, due to civil war and a new military regime in 1991. Since then, the programs in Somalia have been administered by international forces and local women’s organisations.

“Strong traditions and political attitudes are at play here. Female genital cutting is a criminal act in Somalia, but the politicians are either silent when the subject is brought up or they are in favour of the custom. Everybody does it and everybody expects that you have your daughters cut.”

“It is a collective, cultural custom and the price for breaking it is high. Other families won’t let their son marry your daughter unless she is cut,” says Gele.

The men must be involved

In Somalia, the campaigns against FGM have primarily been led by women. Gele concludes in his studies that future campaigns also need to be directed at men.

Without the involvement of men, the chance for success is minimal.

“It is not an easy job for a female Somali activist to talk about the negative consequences of female genital cutting. And it is highly unusual for men and women to discuss the subject together.”

Only opposes to the extreme FGM

The study indicates that campaigns against female genital mutilation only have influenced the practice of the radical type of FGM called infibulation – Pharaonic circumsicion in Somali tradition –which involves the removal of all of the external genitalia and stitching or narrowing of the vaginal opening.

The majority has ceased practicing infibulation, which is regarded as a violation of women’s and girls’ rights.

The Sunna form lives on

But the so-called Sunna form, which involves the removal of the clitoris prepuce, with or without the removal of the tip of the clitoris, is regarded by many as health beneficial.

“Although people interpret the Sunna form, and what it actually involves, differently, there is a clear opposition against its total prohibition. The Sunna form is regarded as a central part of Islam. Thus zero tolerance is regarded as an attack on religion.”

“Many people are aware that female genital cutting ruins sexual pleasure and that many girls leave school due to health related issues as a result of circumcision. But religion is being used as an argument and a justification for practicing the Sunna form, it is like a religious duty,” Gele explains.

Somalis in Norway opposed to circumcision

The interviews with Somalis living in Norway showed that the attitudes have changed. 70 percent were in favour of completely abolishing the custom. The other 30 percent who support the custom had lived in Norway for four years or less, which according to Gele may explain these responses.

“Somalis in Norway have to a large extent altered their attitudes, and this applies to both sexes.“

High status not being cut

According to Gele, a large majority of girls, boys, women and men regard not being cut as a signal of high status.

“This change has taken place over a very short period of time. I would suggest that this illustrates that the right strategy may alter the attitudes towards circumcision in Somalia as well,” Gele says.

Religious leaders

Gele believes that by involving religious leaders in Somalia, it might be easier to achieve successful results.

“According to my studies, it is obvious that the involvement of religious leaders is significant in order to achieve permanent changes.”

“Furthermore, there is a need for political will and wide support from the local community,” he says.

Alternative ritual as strategy

For many ethnical groups, circumcision is a traditional rite of passage symbolising girls’ transition from childhood to adult life. Gele points to Kenya and Sudan, where they in some districts have managed to introduce an alternative ritual where the girls are touched without being injured.

Gele concludes that a similar, locally accommodated strategy directed at the Somali population’s perception of the custom is essential in order to achieve change.

“We need a strategy that people can accept, which does not conflict with religion and marital demands. We need a strategy which can comply with the causes for the continued practice of this tradition.”

-------------

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no

Translated by: Cathinka Dahl Hambro