This article was produced and financed by The Fram Centre

What happens when the forest turns black?

For several years running, the birch forest moth has been wreaking havoc on vast areas of mountain birch forest in the Northern Norway. Scientists are now trying to find out what happens when the moth has eaten its fill.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

A single little bug on its own doesn’t cause much damage, but if they arrive by the millions and one species takes over when the first one quits, the result is many thousands of square metres of black, dead forest.

The culprit is the birch forest moth, and the big problem is that there are several species of it.

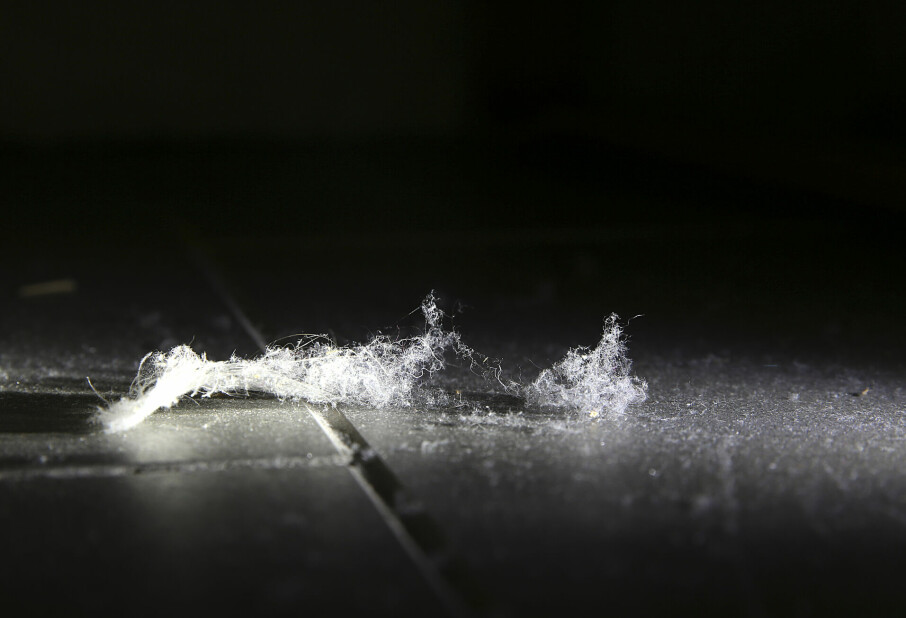

The birch forest moth is a grey-white species in the family Geometridae, whose larvae live in various trees, bushes and herbs.

Until a hundred years ago, the autumnal moth operated all on its own in the north, but with climate change, the winter moth has spread into areas where the autumnal moth used to be the only species of birch forest moth.

The two species have been taking turns tucking in, first the autumnal moth and then the winter moth. And the result is inevitable: stripped of leaves, the forest goes black.

“The trees don’t have time to recover after one attack before they fall victim to attack number two,” says Jane Uhd Jepsen, scientist at the Norwegian Institute for Nature Research at the Fram Centre.

Through a newly established research programme, scientists at the Norwegian Institute for Nature Research and the Department of Arctic and Marine Biology at the University of Tromsø are trying to find out what happens after the voracious birch forest moth has eaten its fill.

Dead forest bears new life

When the birch forest moth attacks, it leaves behind large amounts of dead wood in the forests. That is good news for some.

“These woods constitute a sudden glut of resources for many insect and fungus societies. Along a gradient that stretches from an area with serious outbreaks and a lot of dead wood to an area with healthy forest and little dead wood, we have been collecting insects all summer long in what we call window traps," says Ole Petter Vindstad, research fellow at the University of Tromsø.

The researchers will use the samples to describe the composition of the insect society, and evaluate the importance of such concentrations of resources for the dynamism in selected groups of insects.

Grazing pressure

“We are also looking at how grazing pressure from herbivores impacts the forest’s ability to regenerate after a birch forest moth attack”, says Jepsen.

She and her colleagues have established twelve experimental research plots of 30 × 30 metres, six on each side of the Norwegian–Finnish border, and are comparing the development of the vegetation and forest regeneration in these districts with development in open areas where reindeer have free access.

“In addition, within each of the large research plots, we have set up small research plots where grouse, hares and small rodents are shut out. The sampling areas have been established with a long-term perspective, as natural forest regeneration is a slow process," explains Jepsen.

The research plots will remain for at least 10 years.

Management

In cooperation with FeFo, a company in charge of county-owned land in Finnmark, and the Governor of Finnmark, the researchers have started to look into the importance of management measures that may promote natural forest regeneration, including felling of timber and interventions in the vegetation cover.

“At two locations, we have staked out 20 areas measuring 30 × 30 metres, which will be cut clear this autumn. We will compare the development of the vegetation and the forest regeneration in these areas versus areas that have not been subjected to logging," says Jepson.

“A scarification experiment has also been initiated, where we intervene in the vegetation cover manually and compare natural regeneration from seeds there and in areas that have not been intervened in,” she concludes.