THIS ARTICLE/PRESS RELEASE IS PAID FOR AND PRESENTED BY the Norwegian University of Life Sciences (NMBU) - read more

From displaced children to criminal gang members

How do youngsters forced onto the street by violence and poverty go from being considered vulnerable, displaced minors to feared criminals?

A new study explores this question for a group of street children and youth in the Ugandan city of Gulu. Referred to as the Aguu, these youngsters are labelled as criminal gang members and are considered responsible for much of the violence and crime in the city.

The study traces the origin of the Aguu to the Northern Uganda conflict, a violent clash between the Lord’s Resistance Army (a rebel Christian group) and the government of Uganda that lasted more than two decades.

The conflict uprooted 1.8 million people, two thirds of whom were women and children and was particularly marred by brutality to these groups, resulting in psychological trauma that devastated entire northern Uganda communities. The conflict led to an unusual number of children and youth being forced onto the streets, and so emerged the Aguu.

Where do you want us to go?

Whilst the Aguu are today viewed as feared criminals in the city of Gulu, a report issued by the Human Rights Watch in 2014 (Where do you want us to go?) claims that children living on the streets in Uganda’s urban centres ‘face violence and discrimination by police, local government officials, their peers, and the communities in which they work and live’.

So, should these gangs of children/youth be handled as criminals or victims?

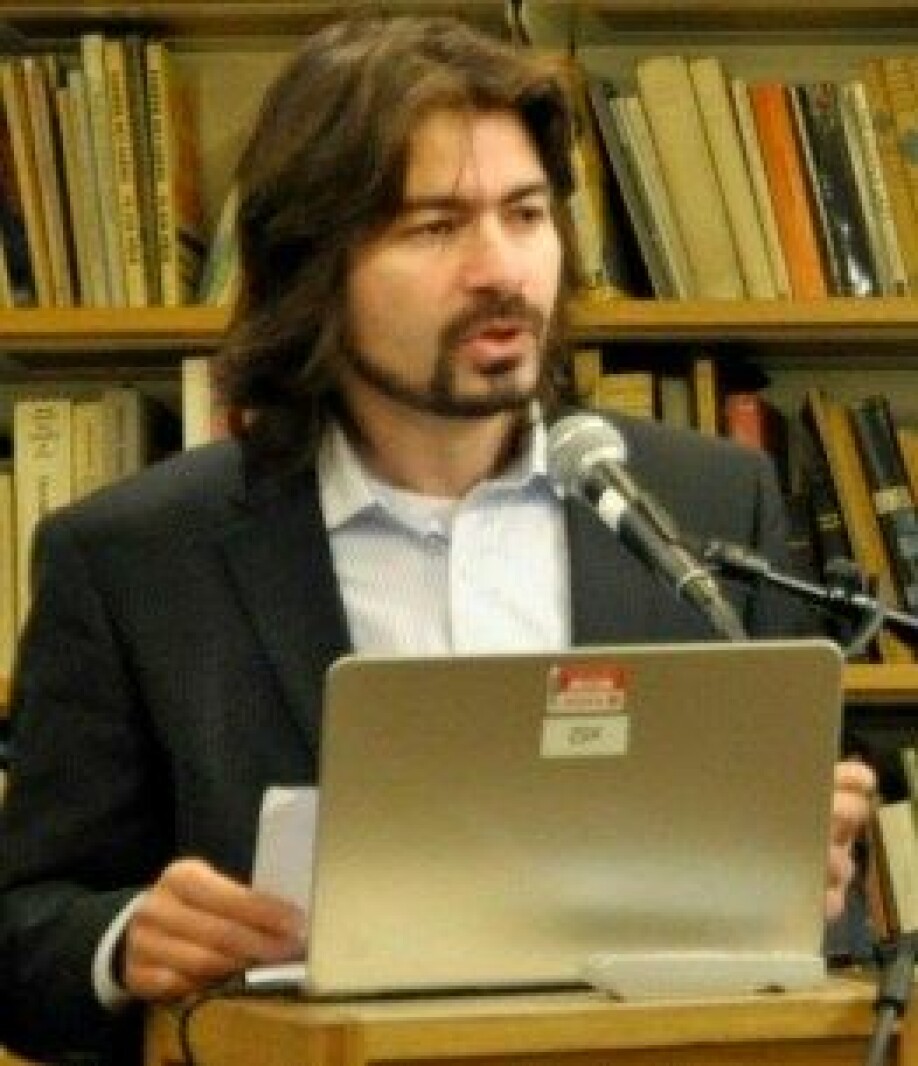

“Very often, there is much more than meets the eye when it comes to blaming crime and insecurity on street gangs. For a real understanding of such issues, those who are quick to label youth/children on the streets as gangs and criminals should be willing to engage in a real attempt to acknowledge the history, economics and politics of the situation, as well as how they may contribute themselves to the persistence of such gangs, and maybe shift to a more compassionate approach to the situation,” says Shai Divon, Associate Professor at the Norwegian University of Life Sciences and lead author of the study.

Together with Arthur Owor from the Centre for African Research in Uganda’s Gulu City, Divon explored the identity of the Aguu, and the details of how they came about.

“I started by asking people in Gulu about the sources of crime and insecurity in the city. The answer I got is that a criminal street gang comprised of children and youth, referred to as the Aguu, is mostly to blame,” says Divon.

“My co-author and I decided to further explore the complex identity of the Aguu as described by themselves and by those who label them as a street gang. We looked into the origins of the Aguu and contrast it with their current identity. We separated the treatment of the group as a deviant entity by the police, political leadership and community in Gulu, from the actual identity of the members of the group. We then tried to identify the various reasons for individual’s presence in the group, why they stayed and how they are organised, including as criminal gangs.”

Is blaming gangs of youngsters such as the Aguu for increased violence and insecurity in post-conflict cities like Gulu not addressing the real issue?

“The Aguu in the streets of Gulu are a result of complex and changing circumstances. The war may have brought children and youth to the streets, but complex mechanisms that we describe in the article have led to the evolution, modification, and persistence of youth/children in the street, and some of these mechanisms have led to increased organisation amongst the Aguu (including criminal organisation),” explains Divon.

“We believe that the mechanisms that led to increased organisation and persistence amongst the Aguu are a result of a complex set of circumstances that include the post-war aid and subsequent growth of Gulu into a city, resulting in various opportunities for youth that were not available to them before,” says Divon. “We also saw political and economic opportunism of members of the community who use Aguu as a reference to rebellious youth in order to support arguments to return to the original culture, or using the Aguu for economic gain, by for example, co-opting them to steal or commit other crimes, or by hiring street children/youth for cheap labour.”

“What we see is that the labelling of groups such as the Aguu that emerge from post-conflict settings like Gulu is not a simple matter of viewing them as deviants from socio-political norms. A complex analysis is needed to have a clearer picture of what is really going on,” he says.

Exploitation of street children and youth

Street children and youth are easily exploited, and the existence of groups such as the Aguu is often perpetuated by the those who also scapegoat them for crime, according to the study.

“There are many different types of activities conducted by those who are labelled Aguu. A so-called Aguu-member can be a member of gang, whilst also selling food, cleaning or working on a farm to make ends meet. Individuals often have very different reasons for ending up on the streets of Gulu.”

“There are many opportunities in a place like Gulu, and there are many reasons why children and youth end up on the streets. Some go to Gulu because they believe they can escape aspects of their cultural constraints. Others want easy money, to feed addictions, to escape difficult circumstances at home, etc. On the streets of Gulu, there are various livelihood strategies and opportunities,” says Divon. “Many of those who argue that the Aguu are a major source of crime and insecurity are also responsible for perpetuating the existence of the Aguu.”

What can be done to improve the plight of street children/youth in post-conflict cities such as Gulu, whilst safeguarding the security of the citizens?

“I don’t think there are magic solutions to these challenges. After all, street youth and children, including those organised as criminal gangs, are found in cities that are not like Gulu, including in rich, non-post conflict and democratic countries such as the US, UK, Germany, Australia, and France. Improvement may be achieved with targeted resources (human and economic) to reach and understand the individual reasons and motivations for every youth/child in the street, and to address these. At the same time, we need to understand and flesh out the historical, institutional, and structural factors within contexts that contribute to the circumstances where children and youth end up on the streets,” says Divon.

“On the police/community side, assuming that the police operate with resources, under the rule of law and without corruption, continuous police presence, along with community and police partnership, may reduce the incidence of crime. The foundations that will allow these mechanisms to make a difference are, however, not present in Gulu today.”

Reference:

Shai André Divon and Arthur Owor: Aguu: From Acholi post-war street youth and children to ‘criminal gangs’ in modern day Gulu City, Uganda, Journal of Human Security, 2021.

See more content from NMBU:

-

Exploring bacteria in Antarctic meltwater ponds

-

Tropical mammals share behavioural patterns across the globe

-

Can Ireland learn to coexist with wildlife again?

-

The sugar industry redefines land and livelihoods of rural people in Ethiopia

-

Humans affect wildlife even in protected areas

-

No safe place: Living on the margins of El Salvador