This article was produced and financed by the University of Bergen - read more

Fascinated by the brain

When Karsten Specht came into contact with brain researchers and language therapists working with aphasia patients, things began to happen.

From that point on, he was totally fascinated by the brain, and especially by the way the brain processes language and acoustic information.

"This has been my main interest for almost 25 years and will probably continue to be so for the rest of my career," Karsten Specht says.

In the project ‘When a sound becomes speech’, they examined the brain processes that lead us to perceive a sound as language. This is an important basis for all verbal communication.

Language in the brain

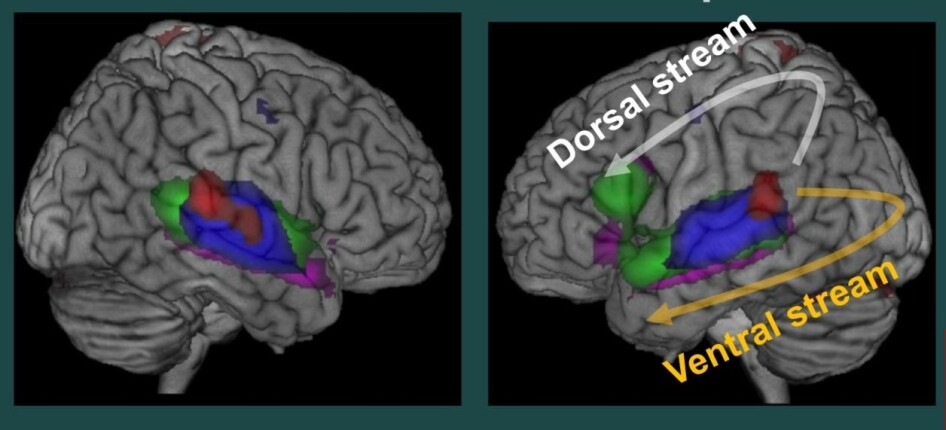

When scientists want to map the language features of the brain, they begin with the premise that languages are organized in a network in different regions of the brain. The regions have several processing units that analyse specific parts of an acoustic, linguistic signal. This analysis occurs before we are able to perceive the sound as language, and before we understand the content.

"But the structure of the network in the brain was not yet fully mapped when we started the project", Specht explains.

At the time, many researchers also thought that language processing occurred almost exclusively in the brain’s left hemisphere. Specht and the research group believed that these processes could be localised and analysed much better using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI).

"If you have a better understanding of these processes, you also have a better basis for examining and treating people with language disorders".

Developed new method

The project developed ‘sound morphing’, a completely new method used to examine language processing, the localisation of processes in the brain and the degree to which the two brain hemispheres are activated. It allows gradually changing individual elements of a sound, while at the same time keeping track of how the brain responds to the sounds.

Several individual studies made it possible to demonstrate that language processing is not a process that occurs only in the left hemisphere of the brain, which is often asserted. It begins on both sides, so that acoustic processing occurs in both halves of the brain. The perception of sentences, grammatical analysis and ultimately understanding of content then gradually move over to be further processed in the left hemisphere of the brain. And the most complex analyses of linguistic communication are done exclusively here.

The movement ("gradient") in the brain's treatment of sound from both brain halves over to the left hemisphere had not been demonstrated before, and was now made possible using this new method.

"All the studies we did in Bergen, Germany and the United Kingdom have given us deeper insight into how the brain processes language, and have showed us how dynamic these processes are".

Brain synapses are important for processing

All brain processes are not conducted in constant and identical ways. In addition, the language network is not a fixed network in which all connections are equally strong all the time. It is dynamically and hierarchically constructed. There are simple processes, such as the way we perceive a vowel, which in turn is different than the processing of a consonant. Then there are other regions in the brain that combine this information and analyse content and meaning. Moreover, all this occurs in only a few milliseconds.

"We showed that children who are in the process of developing or have developed dyslexia, lag a little behind in developing exactly this network", continues Specht.

In patients with aphasia, the research group found that outcomes and severity depend on how much, and especially which parts of the language network remain after a stroke. Some features of the brain can be compensated for; others are difficult to restore through therapeutic training.

Involvement in the treatment of brain damage

Specht’s main motivation has been a strong desire to better understand how the brain processes information, how it adapts to new challenges, and how one can harness these processes to help patients with brain damage. In the Toppforsk project he currently heads, Specht is investigating the underlying neurobiological mechanisms and the fMRI method can be used in the study of the brain. The project will be looking at how this measuring tool can be even further enhanced.

"The fact that studies are largely still being conducted on large-scale sample groups is still a constraint on the fMRI method," Specht says.

He thinks the method needs to be developed in order to draw conclusions about diagnosis and treatment at the individual level, and to be able to adapt the treatment individually.

The grant from the Trond Mohn Foundation laid the groundwork for Karsten Specht's further research. He became a professor immediately after the grant period expired. The research group that was formed produced in excess of ten publications during the project period, and the group is still fully active.