This article is produced and financed by University of Oslo - read more

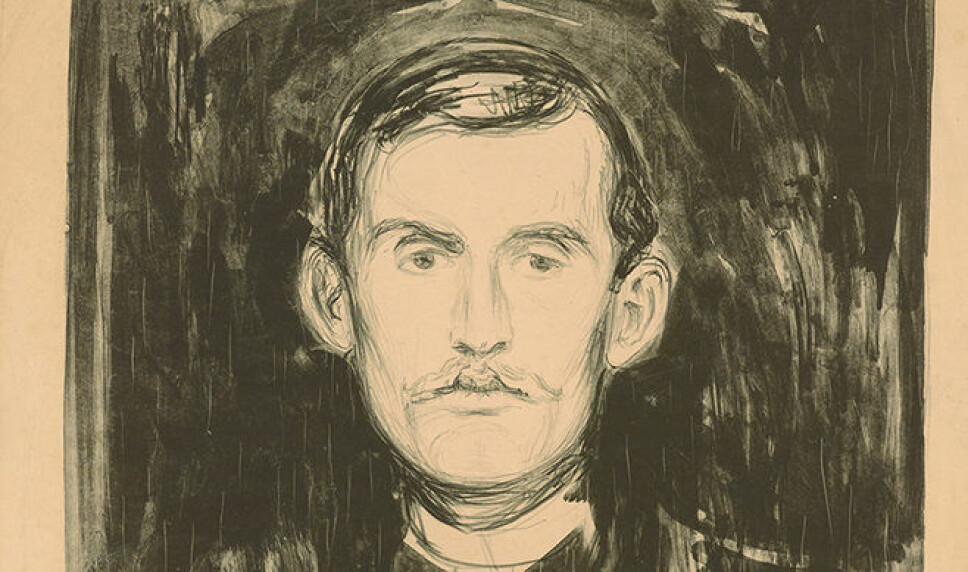

Edvard Munch created myths about himself

Norwegian art historian believes it is time to be more sceptical about the creation of the myth about artists in general, and Munch in particular.

Bohemian and rebellious, lonely and full of anxiety. Partying in the art cafés of Christiania and the bars of Paris and Berlin. Groundbreaking and misunderstood, but celebrated by posterity. This is probably how you are used to thinking about Norway's most famous artist ever: Edvard Munch, the painter and graphic artist.

But why?

“It's hard to say much about Munch as a human being. He is pretty inaccessible behind the biographical concept that we have of him,” says Lars Toft-Eriksen.

Toft-Eriksen has examined how the myth about Munch as an artistic genius has been strengthened and created through the biographies about him. This has resulted in his doctoral thesis entitled Based on a True Story: Rereading Rolf Stenersen’s Image of Edvard Munch and the Myth of Genius. The art historian believes that it is time to be more sceptical about the creation of the myth about artists in general, and Munch in particular.

“The myth about Munch actually holds up, despite 40-50 years of criticism and falsification,” he says.

The man behind the myth is not important

Lars Toft-Eriksen works as a curator at the Munch Museum, where the public are keen to hear stories about Munch.

“I don't think they are necessarily that concerned about Munch as such, but they are looking for something more fundamental, which Munch becomes an example of. They want to be told that the artist is a hero,” he says.

In 1944, the same year that Munch died, the art collector and author Rolf E. Stenersen published his biography entitled Edvard Munch: Close-up of a Genius. According to Toft-Eriksen, there are many biographies about Munch, but this one is still the most important one for how we perceive Munch. New editions keep coming, and it has been translated into a number of languages, most recently Mandarin.

“Stenersen creates a picture of someone who is an original, an eccentric – someone special. He paints a psychological picture, but also describes rivalry with other artists, reinforcing the image of Munch breaking and creating something new.”

Ideology of originality

The fact that the artist is original is fundamental to modern art, according to Toft-Eriksen.

“Although we may not talk about geniuses as much now as we did 100 years ago, the notion of originality is still very strong. Not only in art, but also in science, you have to come up with something new. And what does that really mean? It is an ideology of originality, which influences how we perceive Munch.”

Stenersen describes the genius of Munch by presenting vivid, specific accounts of Munch's life. These are rhetorical ploys that lend literary value to the book, but which, according to Toft-Eriksen, also effectively strengthen the myth about Munch. The book is characterised by ideas and trends that were important in the days of Stenersen and Munch, including psychoanalysis.

“The subconscious is a ‘red thread’ running through Stenersen's concept of genius. It embodies the idea that there is something secret or hidden in the soul or psyche which one does not immediately have access to. In the book there is a sort of leaning towards the irrational, the subconscious, drives, sexuality and desire – versus the rational and the conscious.”

Connection between physics and intellect

“Anyone who saw Edvard Munch would not forget it. His hair was blonde and wavy. He had a rounded, high forehead and greyish blue eyes. His nose and mouth were well-formed despite the fact that he had a narrow lower lip. His chin was powerful, and it seemed even more powerful because he always kept his head up.”

This is what Stenersen wrote in his introduction to Close-up of a Genius, in which he devotes considerable space to describing Munch's physical appearance.

“He compares Munch to Leonardo da Vinci, something which has also been done by other biographers,” says Toft-Eriksen.

Stenersen emphasises Munch’s feminine look and his strange, weak appearance. He pointed out those aspects that deviated from the standards of masculine strength which prevailed at the time, and which, as in the case of Leonardo Da Vinci, served as a testament to his originality.

“Placing physical attributes in the context of intellectual abilities is in line with the scientific field of physiognomy, which can also be linked to phrenology and by extension – the racial theory of the time,” says Toft-Eriksen.

Both physiognomy and phrenology are widely considered to be pseudosciences. The first involves assessing a person's character or personality from their outer appearance, especially the face, while the latter involves the measurement of bumps on the skull to predict mental traits.

In the same way that people in the 1920s explored whether people with different ethnic characteristics had different mental abilities, people wondered if the genius also possessed special physical attributes.

“The German researcher Ernst Kretschmer has written two major treatises about genius. He identifies different body types and devotes a lot of time to August Strindberg and the shape of his head and body.”

Munch's self presentation

Stenersen's biography is based on stories derived from his extensive knowledge of Munch, but also on stories told by Munch himself.

“Munch was certainly aware that he was developing myths about himself, even in his writings,” says Toft-Eriksen.

He refers to notes made by Munch that appeared to resemble diary notes, but which, upon closer inspection, turned out to have been carefully edited and adapted. He believes that Munch's own staging influenced Stenersen's understanding of genius.

“And the myth also had an impact on Stenersen’s understanding of artistic activities. He presented the notion that the artist was a visionary, a prophet, who could look into another reality or the future.”

The myth influencing the art

Munch's art was and still is perceived as being original. But to what extent was it influenced by the myth about Munch being an artistic genius?

“That's how the myth works – it affects how we see Munch's art as being original,” says Toft-Eriksen.

But it is the myth about Munch in concert with the context in which it originated, which is crucial.

“The complex theoretical and aesthetic, but also psychological contexts in which the myth arose, have repercussions for our understanding of his works of art. But this does not just go in one direction, because his works also influences the myths and the ideology.”

“When Munch provoked with the Sick Child in 1886, and his subsequent works in the 1890s in Berlin, he was not just entering the mythology himself, but was also expressing it through his art.”

The artist myth is still strong

Authors help to shape the myth about the subjects of their biographies. Toft-Eriksen believes we should be sceptical about the image being created, but stresses that it does not mean that it is not true.

“The point is that the myth is about more than reality, since it is also about ideology, aesthetics and other historical phenomena.”

For the artists, he believes that the myths have a self-reinforcing effect.

“When you enter into a role, the role eventually becomes real in one sense.”

“How strong is the myth about artistic genius today?”

“I think it's very strong. Perhaps not the older romantic myth, but new myths also arise. Since the days of conceptual art and the 1970s, another myth about artists being bureaucratic figures has also largely prevailed. But it always points back to the myth about artists — that anyone producing creative work is something more than us mere mortals.”

True, reality looks different today, and few people would now associate cheekbones and nose size with how ingenious an artist is.

“But our perception of outward appearance, in terms of gender, sexuality and absent-minded artists, for example, is still present today. Physical appearance is one thing, but the staging of oneself by using gestures and clothing, it is something that some artists are clearly aware of. If you think of a character like Andy Warhol, he is first and foremost Andy Warhol because of his appearance.”

Through his research on Munch, Toft-Eriksen wants to say something about the artist as a cultural figure.

“I think the ideal about the freedom that artists have is important for human self-understanding. From that perspective, the artist has a kind of ideological function for society,” he says.