This article was produced and financed by The Research Council of Norway

Improved seasonal climate forecasts

Arctic sea ice is rapidly retreating. Within a few decades the North Pole could be completely ice-free in summer. How will that affect our weather?

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

In the research project Seasonal Predictability over the Arctic Region (SPAR), scientists have made some discoveries that may lead to more reliable seasonal forecasts. Seasonal forecasting is the prediction of weather over weeks and months, as much as three months ahead.

Seasonal forecasting has proven reliable for tropical regions, but for the Arctic and countries in Northern Europe, forecasts have often been less accurate.

Researchers working on the SPAR project have studied how seasonal forecasts can be improved. They believe this can be done by employing new knowledge about sea ice in the Arctic, snow cover in North America and Eurasia, and special conditions in the stratosphere.

Sea ice is declining

Heat exchange between the oceans and the atmosphere is a main factor in forming weather – and thus for the long-term forecasts of meteorologists. When the ocean in the Arctic is covered with ice, this heat exchange is blocked.

Norwegian climate researchers collaborate with the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF), based in the UK, on global seasonal forecasts.

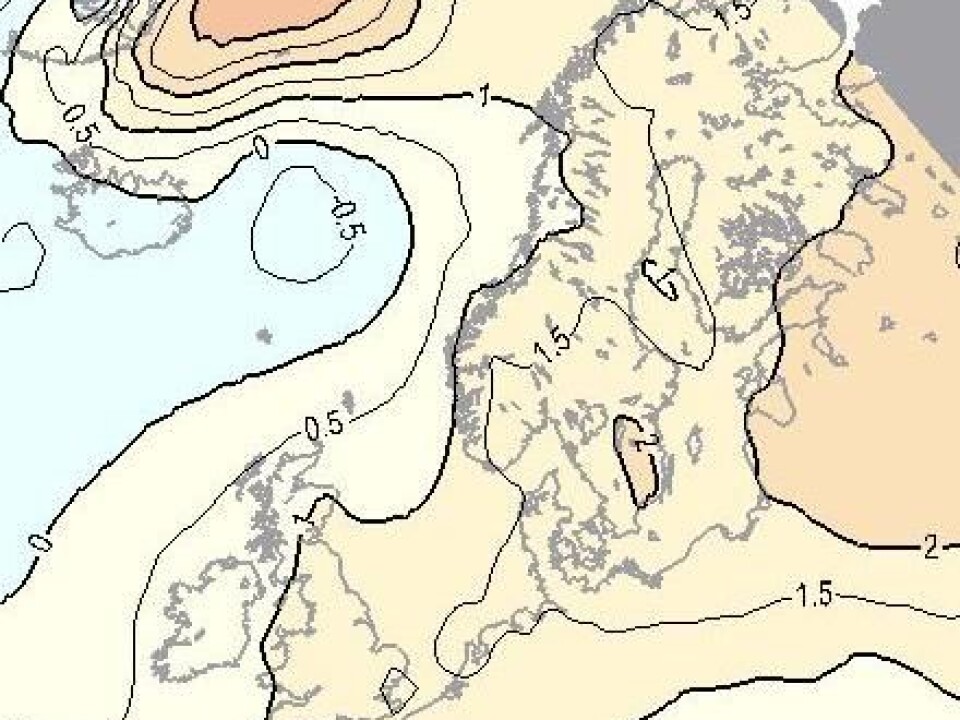

“One problem with the previous global seasonal forecasts from the ECMWF is that they have been based on long-term averages for Arctic sea ice extent," explains Rasmus Benestad, project manager at SPAR and a senior scientist at the Norwegian Meteorological Institute.

"This means the forecasts have not adequately taken the dramatic changes of recent years into account, such as the major reduction in summer ice in the Arctic,”

New calculation methods

Using their knowledge of Arctic sea ice developments over the past eight years, the SPAR project researchers worked out a new way of calculating the role played by sea ice.

The ECMWF has already implemented this new description of sea ice significance into the latest version of its operational seasonal forecasting model.

“The latest version of the seasonal forecasting model predicts a mild winter for 2011/2012. So far, that forecast is holding up,” stated Benestad in mid-January 2012.

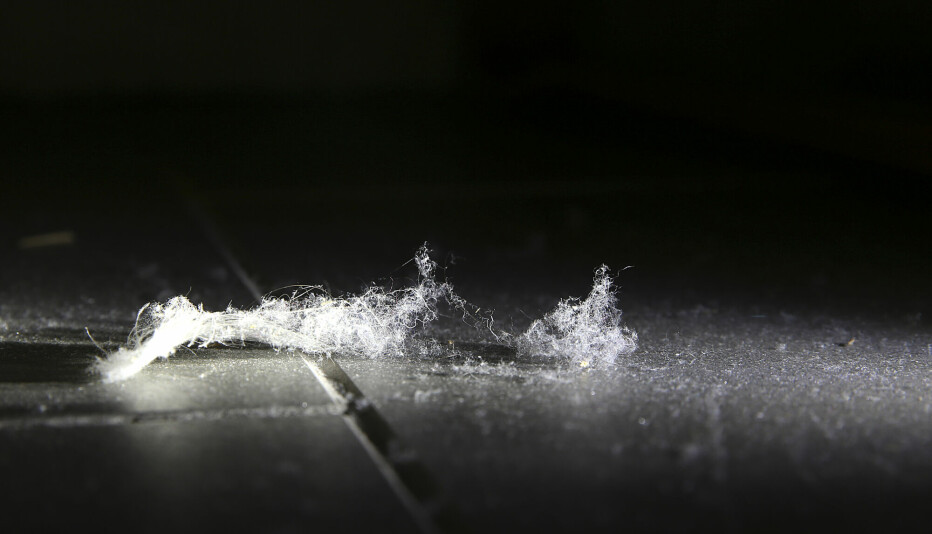

The SPAR researchers also examined the role of snow cover – layer of snow on the ground surface.

Their findings indicate that changes in Northern European and Northern Asian snow cover can indeed affect the weather in the Arctic, most likely by affecting ground temperatures. Changes in snow cover may also have an effect on high-pressure and low-pressure systems over Siberia.

Stratospheric impacts

The third factor the SPAR researchers examined was related to conditions in the stratosphere.

The stratosphere is the second major layer of earth's atmosphere, starting at roughly 10 to 15 km above the surface and continuing up to roughly 50 km. This atmospheric level is very stable – which is why the stratosphere has received little focus as a weather factor until now.

“We wanted to examine this more closely under the SPAR project,” says the researcher. “We ran calculations on models with and without stratospheric conditions included and found that the stratosphere actually has quite a major influence on the weather ahead. So we recommend that the stratosphere be incorporated more actively into seasonal forecasts.”

The stratosphere can play a key role in, for example, the important climatic phenomenon known as the North Atlantic oscillation (NAO) and can have a marked impact on meteorological model forecasts.

The NAO affects Northern Europe’s temperatures, winds and precipitation from late autumn until early spring.

Scientists have known since the 1920s that the NAO is caused by fluctuations in sea-level air pressure between the Azores Low and Icelandic High pressure centres, but until now little was known about what causes these fluctuations. The cold winters of 2009/2010 and 2010/2011 have been explained as anomalies in the NAO.

Factors affect each other

The atmosphere is extremely chaotic. The factors that shape our weather can also affect each other. When two factors are changing simultaneously – such as both sea ice and snow cover – the outcome may be entirely different from what would happen due to changes in just one or the other.

In mathematical terms, the relationships are non-linear. This makes it all the more complicated to predict the weather weeks or months ahead of time.

In the SPAR project scientists used models to run calculations on different ways the factors could affect each other.

"This gave us insight on the impact of sea ice on temperatures here in the North, particularly in the proximity of the Arctic ice. We concluded that more emphasis should be placed on the significance of sea ice in seasonal forecasting, particularly for autumn and winter,” says Benestad.

Translated by: Darren McKellep and Carol B. Eckmann