An article from University of Tromsø – The Arctic University of Norway

Tagging wild salmon into the deep north

The use of satellite tagging has allowed researchers to uncover many of the wild salmon's secrets.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

Wild salmon are tiny compared to the giant ocean they call home, so it is not surprising that we know very little about where they go and what they do when they get there.

But now, researchers working with a project called Salmotrack are using the latest available technology to learn as much as they can about salmon movements in the broad ocean.

"Pop-up satellite tagging"

One of the reasons we know so little about wild salmon is due to their unusual life cycle.

Salmon spend their first few years in a river, with each fish returning to spawn in the same river where it grew up. But it has been very difficult to follow them on their ocean journeys once they leave their home river for the sea.

In recent years, salmon have had increased mortality during the time they are at sea, but much of the explanation for this is due to conditions that we do not understand.

Until recently it was simply impossible to follow these fish during their wanderings in the broad ocean. In contrast, it has been much easier to follow an animal over the water.

“But now we can finally uncover the 'private' lives of salmon in the ocean using satellite technology," says Professor Audun Rikardsen, of the Department of Arctic and Marine Biology at the University of Tromsø.

Rikardsen shows off a small oblong "computer" that can be attached to a salmon's back.

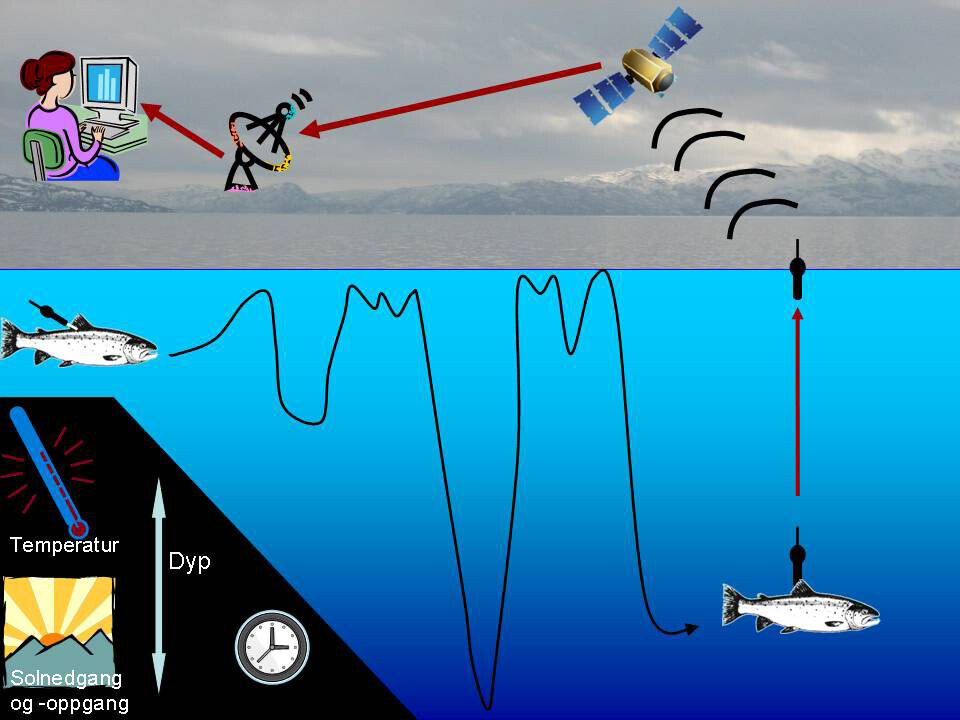

“This hangs on the fish and measures depths and temperatures while they swim. It also records sunrise and sunset,” he says.

The data are then used to figure out where the salmon has been and what it has been doing in the ocean.

The 'computer' is programmed to release from the salmon at a specific time. It then floats to the surface and sends its data and position to a satellite, which in turn sends the data to the researchers.

“That's why it is called 'pop-up satellite tagging'. It's like Christmas Eve when we get into the data − it's just incredibly exciting.”

Along the polar front

Based on the limited data they had, researchers used to believe that when northern Norwegian salmon headed out to sea, they went to the region around the Faroe Islands. But with the help of Salmotrack, researchers now know that this is not usually the case.

Satellite tracking has shown that the salmon spread out over a much larger area in the Barents Sea, along the west coast of Svalbard and in towards Greenland.

Salmon may travel as far as 80 degrees north, which is the most northerly that salmon have ever been recorded. Additionally, the measurements show that salmon swim much deeper than was previously thought.

Rikardsen says the equipment was first programmed to make measurements to a depth of 550 metres because they did not think that salmon swam any deeper than that. But they see that particularly during the winter, when there is less food at the surface, salmon actually swim far deeper than 550 metres.

“It is not inconceivable that they dive significantly deeper than that.”

A preliminary analysis also shows that salmon largely follow the productive zone along the polar front, where the cold water from the Arctic Ocean meets the warm water from the northern extension of the Gulf Stream.

Salmon probably stay in this region because it is where they find the most food.

Since 2008, more than 100 salmon have been tagged, many of which are still swimming around in the ocean right now.

These tagged fish have also been caught by sports fishermen, and several local anglers have aided the scientists in conducting their research.

Fish from northern Norway, Ireland and Greenland have also been tagged, to learn where salmon from these areas go when they are in the open ocean.

Uncovering the salmon's private life

Unfortunately, the future for wild salmon stocks looks rather bleak, and their numbers are steadily declining in Norway.

Nevertheless, the situation for salmon in Norway is better than in the rest of Europe and on the eastern side of North America.

According to Rikardsen this new computer technology will provide important information about the secrets of salmon and other marine animals in the future.

“It is very important for future management to know more about these issues, so that we can make better forecasts and set better quotas. There are six different nations involved in this research," he says.

Doesn't it bother the fish to swim around with that thing on its back?

Rikardsen explains that it would be about the same as if we were to wear a small, lightweight backpack.

Data show that fish grow normally and feel fine even when they are fitted with the satellite tag.

“We are extremely careful in making certain that the tag has minimal effect, because otherwise the data are no good. For that reason, we only tag the biggest fish we can, and have spent a lot of time developing a good tagging method," he adds.

External links

- Audun Rikardsen's profile at University of Tromsø

- SALMOTRACK-project (Electronic tracking of northern anadromous fish)