Ageing: Theory needs to be revised

The existing evolutionary theories of ageing need to be revised, according to a new study, which shows that many of Earth’s plants and animals grow old in surprising ways.

Everything ages – and the older we get, the greater the risk of dying.

This is the popular conception of ageing, but new research suggests that not all species age in the same way – far from it.

A Danish-led group of international scientists has studied the ageing processes of a broad group of animals, including humans, and plants, and the results indicate that the existing evolutionary theories of ageing need to be revised.

The new study demonstrates that for several species, the risk of dying decreases as they age.

Researcher: modify the theory

“According to the classical evolutionary theories of ageing, one would predict that all organisms grow weaker and have an increasing risk of dying as they grow older, just like we see in humans. Many people – including scientists – believe that this applies to all species, but that is not the case,” says ecologist Owen Jones of the University of Southern Denmark, who is the lead author of the new study.

Data from 46 species

In the study, researchers used data from 46 species, including humans, baboons, birds, oak trees, lice, seaweed, crocodiles, killer whales and lions.

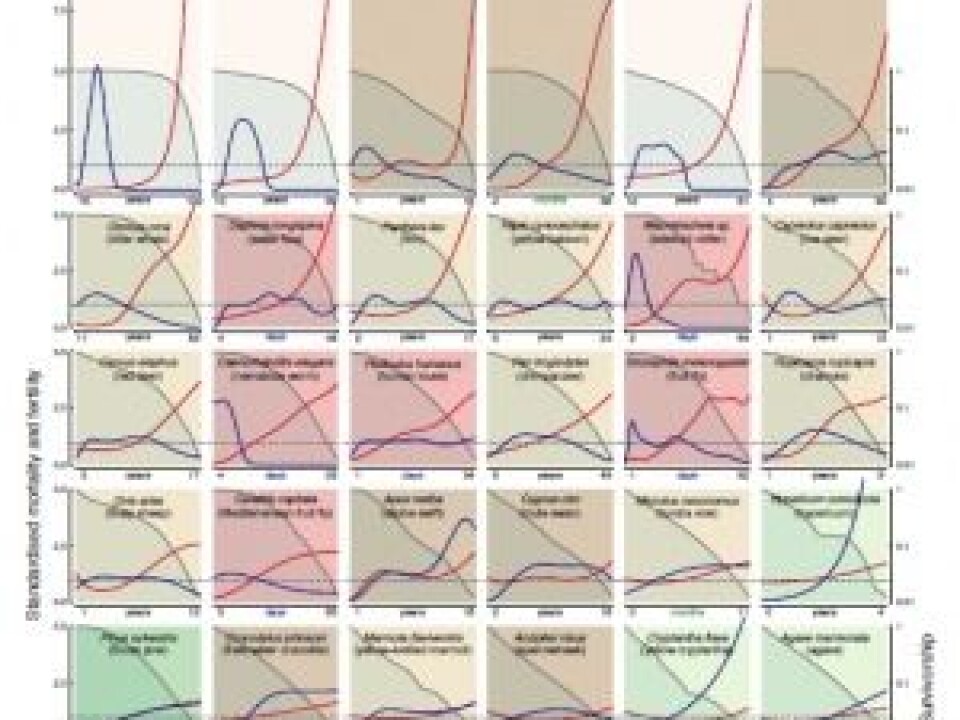

For each of the species, the researchers drew charts of how the mortality and fertility change across the life course of the species.

Existing theories assume that these two parameters follow a fixed pattern: that mortality increases with age, while fertility decreases.

However, having compared their results across the 46 species, the researchers found that this ageing pattern is far from being a universal law of nature.

Some animals do not age

In addition to showing that some animals have a decreasing risk of dying as they age, the study also shows that other species, such as the hermit crab and the freshwater polyp hydra, have a constant mortality throughout their life.

Neither the hermit crab nor the hydra experience bodily decay as they age, and according to the researchers, this can be interpreted as if the animals actually do not age at all.

”The hydra has a constant low mortality throughout its life. In principle, this means that the hydra is biologically immortal. In nature, however, the hydra dies, for example from being eaten by predators,” says Jones.

Crocodiles grow more fertile with age

We have looked at ageing in a wide variety of species from throughout the tree of life. I believe we can learn a lot about how ageing works by looking at the strange deviations from the standard, human-like, way of ageing.

Owen Jones

When it comes to the ability to produce offspring, the researchers also found several exceptions to the existing theories.

Some species actually grow more fertile as they age. In this study, this applied to the freshwater crocodile and several plant species, such as the agave.

The alpine swift, a bird, experiences increasing fertility almost throughout its life, while sexually mature baboons (Papio cynocephalus), on the other hand, maintain a steady ability to produce offspring throughout their lives.

However, when looking at e.g. the Caenorhabditis elegans roundworm, we see an entirely different pattern. According to the study, they are actually fertile from early in life, after which they very quickly lose the ability to have offspring.

Ageing remains a mystery

This turns our conception of ourselves on its head: we do not age slowly; we actually age very quickly.

Owen Jones

According to Jones, the different patterns of mortality and fertility show that ageing remains a poorly understood phenomenon:

”In our study, we have looked at ageing in a wide variety of species from throughout the tree of life. I believe we can learn a lot about how ageing works by looking at the strange deviations from the standard, human-like, way of ageing.”

Humans age quickly

One of the most surprising findings was that out of all the species featured in the study, humans age the quickest.

”As modern humans, we do not regard ourselves as organisms that age particularly quickly compared to species like mice or other animals. But out of all the species we studied, humans were the species that ages most quickly, in relative terms.”

It may seem a bit odd that humans age more quickly than e.g. the fruit fly, which has a lifespan of only a few months.

Jones explains this referring to the new standardised chart that his research team has developed, which enables them to compare mortality and fertility across species – despite the species having highly different average lifespans.

On this chart, humans have the steepest mortality curve of all the 46 species.

Study revolutionises our view of humans

”If, for instance, we look at the hydra, we see that its risk of dying remains constant throughout its life. For humans, on the other hand, the risk of dying increases 20-fold when we grow old, compared to the average risk of dying throughout life," he says.

This turns our conception of ourselves on its head: we do not age slowly; we actually age very quickly."

The prevailing theory of ageing

The existing evolutionary theories that explain why animals and plants age were developed back in the 1950s and 1960s.

In short, the theories state that all species, including humans, invest solely in their own survival until they are sexually mature.

After that, investment in reproduction becomes more important even at a cost of their own maintenance and survival. A consequence of these theories is that the body starts to age, or decay, from when the individual becomes fertile.

No new theories have solved the ageing mystery

The researcher says that it may not make much sense that evolution has not come up with a way of preserving the body and preventing ageing, especially considering that building an organism in the first place is such a complicated and impressive task.

“Up to now, the explanation has been that we are presented with the choice between investing our resources in reproduction here and now, or investing them in preserving our bodies and repairing damage,” he says.

“There is an advantage in reproducing as quickly as possible is if you risk dying in an accident, or by predation, tomorrow. This is one of the main points in the evolutionary theories of why we age.”

However, the new study shows that this prevailing theory is far from complete:

”If the theory were correct for all species, we would expect that the risk of dying would increase after sexual maturity for every species. In other words, we would see a pattern of a gradual reduction in survival probability after reaching sexual maturity for all species. But this is not the case. Far from it,” says Jones.

The researchers behind the new study do not, however, have a full-fledged theory that can replace the prevailing ones. This means that the question of why most life on our planet ages and dies remains an unsolved mystery.

--------------------------

Read the Danish version of this article at videnskab.dk

Translated by: Dann Vinther