Is nursing not for boys?

Gender stereotypes in preschool surprise researchers

Children believe it is primarily women who can become nurses and preschool teachers. “A nurse is unbelievably many different things,” says nurse Remi Trygve Pedersen.

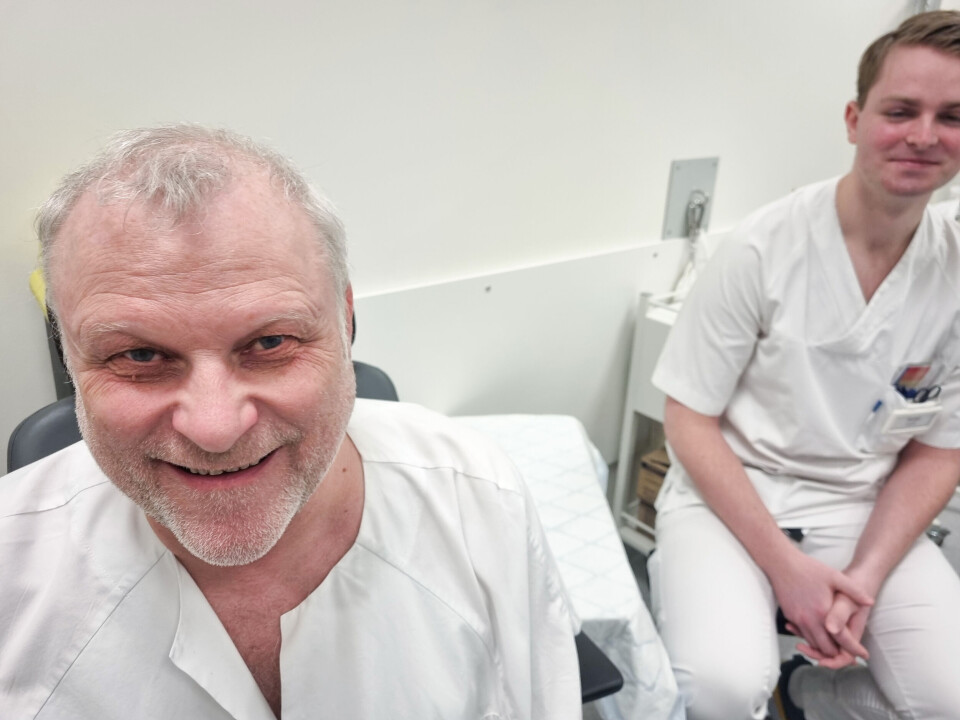

“Suddenly, you’re informed that another patient needing urgent care is coming, and you have to leave the first one, both mentally and practically. Then you have to start over,” Sander Frise says.

When nurse Frise is at work, he must act quickly, handle stress, and perform his duties without hesitation.

Sander works in the emergency department at Kongsberg Hospital. He talks about the everyday life at the department. They are hectic, stressful, and can sometimes be quite painful. While other days can be calmer, governed by routine, and even a bit boring.

“This is part of the excitement of working in the emergency department. You never know what the day will bring,” says colleague Hans Lind.

10 per cent male nurses

It is not so common for men to work as nurses in Norway, like Sander Frise, Remi Trygve Pedersen, and Hans Lind. Only 10 per cent of nurses are men. The same applies to preschool teachers, according to Utdanning.no (link in Norwegian).

How is it that the gender divide is so strong in Norwegian working life?

It turns out that children already in preschool have a notion of what girls and boys should work with. This is revealed in a doctoral thesis from UiT The Arctic University of Norway.

What do children want to be when they grow up?

What thoughts do Norwegian children have about the future and opportunities in working life? Marte Olsen wanted to find out.

“We see it quite early, already when the kids are about four years old,” Olsen tells sciencenorway.no.

What she sees are gender stereotypes. These are ideas about what it means to be a woman, man, or other gender.

Olsen's research shows that they influence what children want to be when they grow up – from when the children are quite young.

Boys who believed that nurses and preschool teachers are mostly women were less interested in becoming that themselves. At the same time, girls who believed the same were more interested in becoming that.

“These gender differences fit well with the gender division that exists in the job market today,” says Olsen.

Does nursing solely revolve around caregiving?

How can young boys know so early that these occupations are not for them?

This belief is influenced by adults' perceptions of what constitutes a typical nurse or preschool teacher, according to Olsen.

“When we think about traits that are important in occupations, such as nursing and preschool teaching, we often think of being caring, warm, and friendly. And that caregiving is something primarily done by women,” she says.

We adults talk about nurses and preschool teachers in ways that make boys think these occupations are not suitable for them, according to Olsen.

"And we also know that being warm and caring is not the only thing important for being a good nurse; you also need to be efficient, organised, and good at calculating medications," she says.

“If we describe nurses more with these traits, maybe more boys would feel that this is a occupation suitable for them.”

Olsen has also studied how nursing students perceive themselves. There, she found that male students who see themselves as less caring and warm also feel less connected to their studies and that they do not fit in.

“That makes them more likely to consider dropping out of their studies,” Olsen says.

Many aspects of care

When Sander Fris was studying nursing, he learned that ‘everything is care’.

“It can be anything from fetching water or adjusting a pillow, to administering the correct medications or simply saving lives,” he says.

There are clearly a lot of things encompassed by the concept of care. To qualify as a nurse, for example, you need to calculate how much and what kind of medication the patients should have, take blood samples, perform life-saving procedures, administer injections, do heavy lifting, and work at both a slow and fast pace.

All of this is done in the emergency department, according to the nurses.

Action in the intensive care unit

“Life as a nurse in an emergency department is probably a bit different from being a nurse elsewhere,” says Remi Trygve Pedersen. He has worked in the emergency department in Kongsberg for over 20 years.

“It’s maybe a bit more action-packed here.”

Sander does not quite agree. He thinks many girls are interested in action, for example, in the intensive care unit or as an operating room nurse.

“And it's not just action here,” Remi points out. “If it had only been severely ill patients, blood and gore all the time, the stress level would have been so high that we couldn’t have managed it.”

Need good role models

Marte Olsen believes part of the explanation for the early gender stereotypes might be that boys lack role models in occupations like nursing and preschool teaching.

“In preschools, the kids see that it’s mostly women working there. Therefore, it’s important to get more men in there so that the children can see that it’s actually possible to be a male preschool teacher,” she says.

The occupations that children encounter in their daily lives are typically female-dominated occupations, according to Olsen. They meet nurses at the health centre, preschool teachers in preschool, teachers at school, dental hygienists at the dentist, and so on.

Asked children in preschool questions

The studies conducted by Marte Olsen and her colleagues included 159 preschool children in Tromsø, northern Norway, and 96 primary school children from across Norway.

The researchers asked the younger children questions in small groups, while those in primary school responded to questionnaires.

It was here that Olsen found a correlation. Both in preschool and primary school, gender stereotypes appeared to be linked with what the children wanted to be when they grew up. If the boys believed that nursing or preschool teaching were occupations for women, they were less likely to want to pursue them.

Boys who did not hold these beliefs were just as likely as girls to consider becoming nurses or preschool teachers.

Based on these studies, Olsen cannot conclusively state that gender stereotypes determine career aspirations or choices. However, her findings align well with both theory and earlier research.

“It's a reasonable assumption that a boy who has been told that nursing is a woman's job will less likely envision himself as a nurse one day,” she says.

Why nursing?

The nurses at Kongsberg Hospital chose the occupation for slightly different reasons.

Remi Pedersen is actually trained as a commercial pilot.

“But I needed a occupation where I was 100 per cent guaranteed a job. It doesn't pay very well, but at least there is money coming in,” he says.

Hans Lind stumbled into the occupation after working with agriculture and animal husbandry. He started in psychiatry and eventually studied to become a nurse.

“If you like working with people, this is a very good occupation. I can't imagine sitting in front of a computer for eight hours every day,” he says.

For Sander Fris, it was different.

“The reason I became a nurse is a bit random,” he says.

Sander had a rough understanding of his career path due to his prior experience working in nursing homes and with patients.

“Still, you never know what you're getting into. Many probably know little about what nursing is. However, if your goal is to work closely with people and make a difference, while also finding the subject interesting, then this is a good job,” he says.

Surprised by the results

Hilde Gunn Slottemo is surprised by Olsen's results, which show that children already in preschool have an idea that some occupations are for girls and some are for boys.

Slottemo is a historian and professor at Nord University. She has researched gender in the workplace, among other things.

She explains that there is a difference in how men work in female-dominated occupations, and vice versa.

“When women enter men's occupations, they do so with pride. If they become doctors, they enter a occupation with high status, high pay, and considerable prestige. This move is viewed positively, with women generally advancing in their careers,” says Slottemo.

The situation is quite different for men moving into fields predominantly occupied by women.

“Rather than ascending, their career trajectory tends to descend. They end up in positions known for lower pay, lesser status, and less prestige,” she says.

Slottemo mentions male preschool teachers as an example.

“They don't want to dabble with beads and drawing or read to the kids. They want to go out and climb the trees, and engage in tough, masculine games with the kids,” says Slottemo.

“They wish to be preschool teachers in their own way.”

It’s about status

According to Slottemo, it’s all about status.

“Precisely because female-dominated occupations have low status and pay, men want to give the impression that they’re doing something different from the women,” she says.

“But for the women, it’s the opposite. They enter male-dominated fields aiming to gain from the higher status these occupations often hold.”

Significant progress has been made

“Why does such a gender divide exist in the workforce of one of the world's most egalitarian countries?”

“Perhaps we’re not as egalitarian as we think, mainly because the gender divide in our workforce still exists,” Slottemo answers.

Howver, she believes that a lot has changed in just a few generations.

“Women have entered the workforce and become financially independent. And it’s actually the case that occupations change gender,” she says.

Just a generation ago, it was always women who worked in stores. Today, it’s just as common to see young men behind the counter, she notes.

“And the idea that you could have a male nurse was completely unthinkable not too long ago,” Slottemo says.

Sykepleien.no (link in Norwegian) reports a record number of male nursing students in Southeast Norway. Now, over 13 per cent of nursing students at the University of South-Eastern Norway are men.

“So, it’s clear that significant changes have occurred, even though much remains the same,” she says.

Thousands of nurses needed

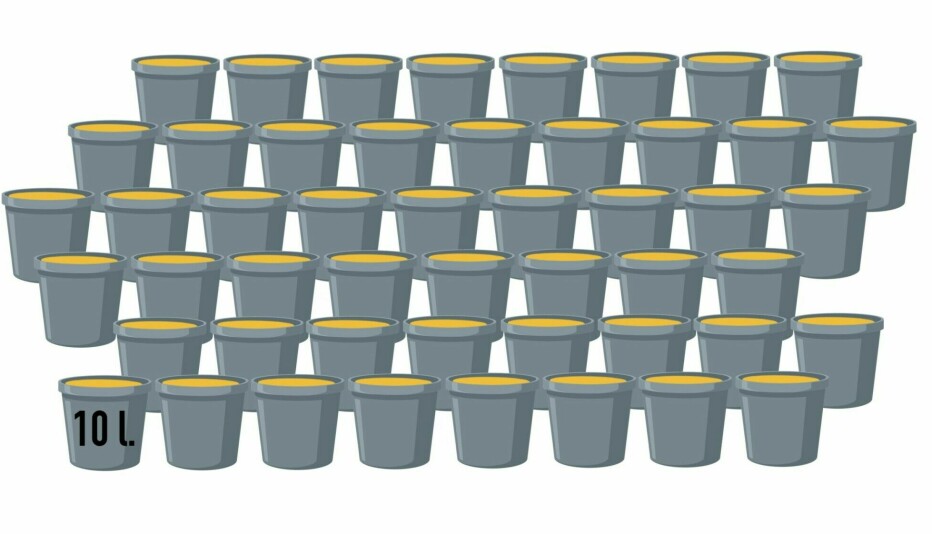

Norway currently lacks 4,650 nurses, 600 nurse practitioners, and 100 midwives, according to figures from the Norwegian Labour and Welfare Administration (NAV).

Therefore, we must prevent stereotypes from developing so early, according to Olsen.

She believes we need to talk about these occupations differently, increase their status, and get more men involved.

To raise the status, salaries must also increase.

“The salaries for caregiving occupations need to be raised to make these jobs more attractive to young people,” says Olsen.

Demand for higher salaries

The nurses at Kongsberg Hospital also emphasise what is necessary for more men to want to become nurses.

“I would definitely recommend the occupation, but I think the authorities should do something about the salary and working conditions,” says Hans.

Hans talks about companies in Kongsberg, located near the hospital, that hire newly graduated students from computer science and engineering studies. They receive a starting salary much higher than that of nurses, according to Hans.

“If nothing is done about this, I don't think people will choose to become nurses,” he says.

“Good working conditions are just as important. We need enough staff on the wards to do what needs to be done. Many have to work overtime, there are few substitutes, and we have to cover for each other,” says Remi.

———

Translated by Alette Bjordal Gjellesvik

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no

Reference:

Olse, M. Men's Underrepresentation in Communal Occupations: A Social-Developmental Approach. Doctoral thesis at UiT The Arctic University of Norway, 2023.